Adolescents and Psychiatric Medications: How to Monitor for Suicidal Ideation

Adolescent Suicide Risk Monitoring Tool

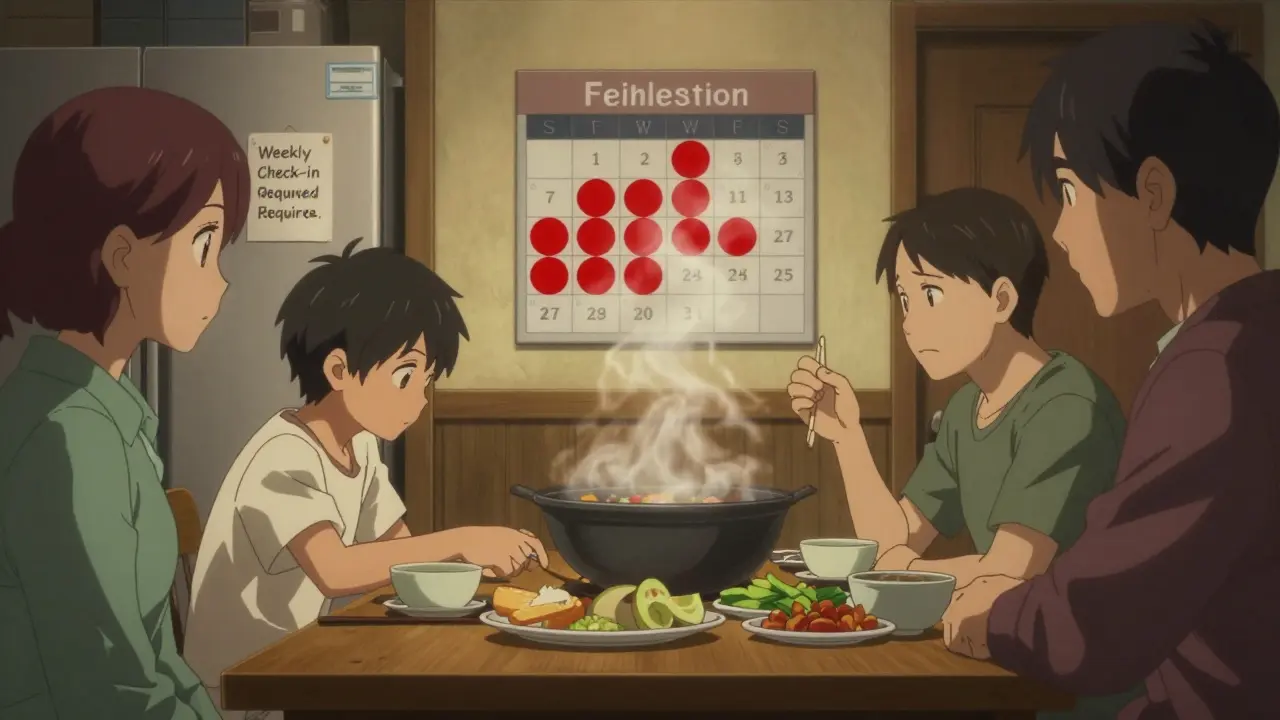

Critical Monitoring Period

This tool assesses warning signs during the highest-risk period (first 4 weeks of starting or changing medication). Always consult your healthcare provider for professional evaluation.

When a teenager starts taking psychiatric medication, the goal is relief - less anxiety, better sleep, fewer mood crashes. But for some, the very drugs meant to help can trigger something dangerous: suicidal ideation. This isn’t rare. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable - if you know how to watch for it.

Why Adolescents Are at Higher Risk

Teens aren’t just small adults. Their brains are still wiring themselves, especially the parts that control impulses and weigh consequences. When a medication like an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) hits the system, it can cause a sudden shift in neurotransmitter levels before the brain adapts. This mismatch can lead to agitation, restlessness, or worsening sadness - not because the drug isn’t working, but because it’s working too fast. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a black box warning on antidepressants in 2004 after data showed a small but real increase in suicidal thoughts in kids and teens during the first few weeks of treatment. That warning still stands. And it’s not just antidepressants. New research shows similar risks can appear with antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and even stimulants used for ADHD - especially when started or changed.When the Risk Is Highest

There’s no mystery about when to watch. The danger window is narrow but critical:- First 1-4 weeks after starting a new medication

- Within 2 weeks after increasing the dose

- During tapering or stopping - this is often overlooked

What Monitoring Actually Looks Like

Monitoring isn’t a checklist you fill out once a month. It’s a rhythm. A daily awareness. Here’s how it works in practice:- Weekly check-ins for the first month - even if the teen seems fine. Ask direct questions: “Have you had thoughts about not wanting to be alive?” Not “Are you sad?” - that’s too vague.

- Track behavior changes - Is the teen suddenly more agitated? Sleeping less? Talking less? Giving away things? These are red flags.

- Involve the family - Parents and caregivers need to know what to watch for. Give them a simple list: sleep changes, irritability, talking about death, sudden calm after deep depression.

- Use standardized tools - The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is free, validated, and used by clinics worldwide. It asks clear, non-leading questions that reveal risk levels.

- Document everything - Not just “patient stable.” Note: “Patient reports no suicidal thoughts today. Sleep improved from 4 to 6 hours. Still avoids school. No new self-harm.” Specifics matter.

The Discontinuation Trap

Many clinicians focus on starting meds - but stopping them is just as risky. When a teen feels better, families often want to quit. But pulling the plug too fast can trigger withdrawal symptoms that mimic depression or anxiety - and sometimes, suicidal thoughts. California’s 2022 guidelines say it plainly: if a teen was suicidal before starting medication, you need a taper plan before you even begin. That means:- Slowing the dose down over weeks, not days

- Increasing monitoring frequency during taper - weekly or even twice weekly

- Watching for rebound symptoms: insomnia, nightmares, panic, hopelessness

Who Should Be Watching?

This isn’t just the psychiatrist’s job. It’s a team sport:- Parents - They see daily changes. They need training, not just a handout.

- School counselors - 68% of them report not being told when a student is on psychiatric meds. That’s a gap. Schools and clinics need shared protocols.

- Primary care doctors - Many teens see their pediatrician more than their psychiatrist. They need to know the warning signs.

- The teen themselves - They must feel safe to say, “This isn’t helping. I feel worse.” That only happens if they’ve been told, clearly and repeatedly, that their feelings matter - even if they’re scary.

The Consent Problem

You can’t monitor what you don’t discuss. Yet a 2021 survey found that 42% of child psychiatry fellows felt unprepared to explain suicide risk as part of informed consent. Parents often hear: “This medication helps depression.” They don’t hear: “In the first few weeks, it might make thoughts of death stronger - and we’ll check weekly to catch it.” That’s not malpractice. It’s avoidance. But it’s dangerous. Real consent means naming the risk. Not burying it in fine print. Saying: “We’re starting this because your depression is severe. But we know it can sometimes make suicidal thoughts worse - so we’ll see you every week for the first month. If you feel worse, we stop or adjust. No shame. No judgment.”

What’s Missing in Practice

There’s a gap between what guidelines say and what happens in real clinics:- Only 57% of outpatient child psychiatry practices have standardized suicide monitoring protocols.

- Only 34% of child psychiatry residents get 8+ hours of training in suicide risk monitoring.

- Just 19% of digital risk tools are designed to track medication-related suicidal ideation - most just ask, “Are you thinking of suicide?” without context.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re a parent, caregiver, or provider:- Ask the prescriber: “What’s the plan if my child feels worse?”

- Get the C-SSRS form - it’s free at Columbia University’s website. Use it at home.

- Keep a journal - note sleep, mood, energy, school attendance. Patterns show up over time.

- Don’t wait for crisis - If your teen says, “I wish I wasn’t here,” take it seriously. Call the prescriber immediately. Don’t wait for the next appointment.

- Push for communication - Between school, clinic, and home. One shared note. One shared contact. One plan.

The Bigger Picture

Medication isn’t the enemy. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it can help - or harm - depending on how it’s used. The goal isn’t to avoid meds. It’s to use them wisely. With eyes open. With plans in place. With people watching. The data shows that when teens get proper monitoring, suicide rates drop. Not because the meds magically fix everything - but because someone was paying attention. Someone asked. Someone listened. Someone acted. That’s what matters.Do all psychiatric medications carry a suicide risk for teens?

Not all, but many do. Antidepressants have the strongest evidence and the FDA black box warning. But research now shows that antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and even stimulants can trigger suicidal thoughts in vulnerable teens - especially during the first few weeks or when doses are changed. Monitoring should be standard for any psychiatric medication started in adolescence.

How often should a teen on psychiatric meds be checked for suicidal thoughts?

Weekly for the first 4 weeks after starting or changing a dose. After that, every 2-4 weeks for the first 3 months. If the teen has a history of suicide attempts or severe depression, weekly monitoring may continue for 6 months or longer. During tapering, return to weekly or more frequent visits. Never assume stability - check in regularly.

What if my teen says they feel worse after starting medication?

Don’t wait. Call the prescriber immediately. This is not a sign the medication isn’t working - it’s a warning sign that the brain is reacting. The prescriber may lower the dose, switch meds, or add support like therapy. Stopping abruptly can be dangerous. But ignoring it can be deadly. Always act fast.

Can therapy replace medication for suicidal teens?

Therapy - especially CBT or DBT - is essential and should always be part of treatment. But for teens with severe depression, anxiety, or psychosis, medication can be necessary to create the stability needed for therapy to work. They’re not alternatives - they’re partners. The best outcomes happen when both are used together, with careful monitoring.

Are there signs I can watch for at home?

Yes. Watch for: sudden calm after deep sadness, giving away prized possessions, talking about being a burden, sleeping too much or too little, withdrawing from friends, increased irritability, or writing about death. These aren’t normal teen mood swings. They’re warning signs. Document them. Share them with the prescriber.

What if the school doesn’t know my teen is on medication?

Schools are often the first to notice changes in behavior - but they can’t help if they don’t know. With your permission, share a brief note from the prescriber explaining the medication and warning signs to watch for. You don’t need to disclose the diagnosis. Just say: “My child is on a medication that can sometimes cause increased sadness or agitation. Please alert me if you notice changes in mood, behavior, or talk of self-harm.” This builds safety nets.

Is it safe to stop the medication if my teen feels worse?

Never stop abruptly. Sudden withdrawal can cause rebound depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts. Always work with the prescriber to create a slow taper plan. Even if you want to stop, do it step by step - with weekly check-ins. The goal isn’t just to remove the drug - it’s to protect your teen’s safety while doing it.

Jessie Ann Lambrecht

January 7, 2026 AT 07:05Finally, someone says it like it is. I’ve been a pediatric nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen too many kids crash because everyone assumed ‘they’re fine’ just because they stopped crying. Monitoring isn’t optional-it’s the difference between life and a obituary. Use the C-SSRS. Print it out. Tape it to the fridge. Ask the hard questions every damn week. No excuses.

And parents? Don’t wait for the appointment. If your kid says ‘I wish I wasn’t here,’ call the doc. Right now. Not tomorrow. Now.

Aparna karwande

January 8, 2026 AT 17:46How can you even let children take these chemical weapons? In India, we raise our kids with discipline, yoga, and family meals-not pills that turn their minds into glitchy video games. This is Western medical arrogance at its worst. You don’t fix emotional pain with serotonin tweaks. You fix it with values, structure, and respect for elders. This post reads like a pharmaceutical ad with footnotes.

Adam Gainski

January 9, 2026 AT 10:09Great breakdown. I’m a school counselor and I’ve seen the gap between clinic and classroom firsthand. The biggest problem? No one tells us. I had a kid withdraw, start sleeping at his desk, and hand in essays about drowning. I had no idea he was on an SSRI. If clinics would just send a one-page alert with warning signs, we could catch things early. No diagnosis needed-just ‘medication in use, monitor for behavioral shifts.’ Simple. Safe.

Also, yes to the C-SSRS. I use it weekly now. It’s not scary-it’s structured. And kids open up to it way more than to ‘Are you okay?’

Anastasia Novak

January 11, 2026 AT 00:00Oh my god. I’m so tired of the ‘just talk to them’ advice. Like teens are little therapists who just need the right prompt. No. They’re wired differently. And when meds hit their neurochemistry mid-puberty? It’s like throwing a lit match into a room full of fireworks. And the system? Still using paper forms from 2007. I work in ER. I’ve seen the aftermath. We don’t need more awareness. We need mandatory protocols. Every prescriber. Every school. Every parent. No exceptions. This isn’t ‘being careful.’ This is survival.

Elen Pihlap

January 12, 2026 AT 00:31My son started on fluoxetine and became a monster. He screamed at me for 3 hours straight because I moved his socks. I thought it was puberty. Then I read this and realized-oh my god, it was the med. I called the doc right away. We lowered the dose. He’s better now. But I wish someone had warned me before it got this bad. Please, if you’re reading this-don’t wait. Don’t assume. Don’t hope. Act.

Sai Ganesh

January 12, 2026 AT 19:20As someone raised in a family where mental health was never discussed, I’m grateful for this. In India, we say ‘be strong’ and ‘it’s all in your head.’ But this isn’t weakness. It’s biology. And monitoring isn’t spying-it’s love in action. I’ve started using the C-SSRS with my niece. She didn’t want to talk, but she wrote down ‘I feel empty’ on the form. That’s progress. Thank you for making this practical.

Paul Mason

January 13, 2026 AT 09:52Look, I get it. But let’s be real-most of these kids are just being dramatic. I was a teen in the 90s. We didn’t have SSRIs and we still made it. Now everyone’s on something. You give a kid a pill and suddenly they’re a walking crisis. Maybe the real issue is we’ve stopped teaching resilience. Just saying.

Katrina Morris

January 14, 2026 AT 16:39i just wanted to say thank you for writing this. my sister is on meds and we’ve been so scared to ask the right questions. we printed the c-ssrs and now we do a quick check every sunday night. she says it feels less scary now. i dont know much about this stuff but i know love matters. and paying attention. thats it.

ps sorry for the typos im typing on my phone

steve rumsford

January 14, 2026 AT 23:32My cousin was on Adderall. Got worse. We thought it was ADHD getting worse. Turns out the stimulant was frying his nervous system. He started texting ‘I wish I could disappear’ at 2am. We didn’t know what to do. Called the doc, they said ‘give it time.’ He ended up in the hospital. Now he’s on a slower taper. And we have a plan. Don’t let ‘give it time’ be your answer. Time kills when you’re in crisis.

Andrew N

January 16, 2026 AT 04:25Statistically, the risk is low. Like 1-2%. This post is fearmongering. Most teens on SSRIs don’t become suicidal. The black box warning was based on old data. Modern studies show the benefits outweigh the risks by 5:1. You’re scaring parents into avoiding treatment for real depression. That’s worse than the risk.

LALITA KUDIYA

January 17, 2026 AT 05:18thank you for this ❤️ my brother is on mood stabilizers and we were so scared to talk about it. now we have a weekly check-in. no pressure. just ‘how’s your head today?’ and a cup of tea. he says it helps. i dont know all the science but i know silence kills. this is good

Poppy Newman

January 18, 2026 AT 05:03OMG YES. I’m a therapist and I use the C-SSRS with every teen on meds. It’s the only tool that doesn’t feel like an interrogation. And the best part? Kids actually fill it out. One girl wrote ‘I feel like a ghost’ on the ‘hopelessness’ line. We caught it. She’s in DBT now. 🙏

Also-parents, PLEASE share the plan with schools. I had a student collapse in class because no one knew she was tapering off an antipsychotic. We were lucky she didn’t hurt herself.

Anthony Capunong

January 19, 2026 AT 01:29Whoa. This is just another way for the medical-industrial complex to profit. You think teens are broken? No. They’re reacting to a society that gives them nothing to live for. Screens. Pressure. No jobs. No hope. You give them a pill and call it a fix? That’s not treatment. That’s suppression. Let them feel. Let them rage. Don’t drug them into silence.

Vince Nairn

January 20, 2026 AT 05:06Wow. So the solution to America’s teen mental health crisis is… more paperwork? Congrats. You turned a human tragedy into a checklist. I’ve worked in three ERs. The kid who says ‘I’m fine’ while staring at the ceiling? The one who gives away his Xbox? The one who stops laughing? You don’t need a form. You need eyes. And heart. And someone who shows up. Not a protocol. A person.

Ayodeji Williams

January 21, 2026 AT 20:43bruh why are we even doing this? teens be like ‘i hate life’ every other day. i had a cousin say that then went to the mall and bought new sneakers. this is just woke culture making everything a crisis. give em a hug and tell em to stop being soft