Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Intervals and Treatment Options Explained

Diabetic retinopathy isn't just a complication of diabetes-it's the leading cause of preventable vision loss in adults under 65. If you or someone you know has diabetes, ignoring eye health isn't an option. The good news? With the right screening and timely treatment, 98% of severe vision loss from diabetic retinopathy can be avoided. But knowing when to get screened and what treatments actually work is confusing. Annual eye exams aren't always necessary, and not all treatments are created equal. Here’s what you need to know, based on the latest evidence and real-world practice.

How Diabetic Retinopathy Develops

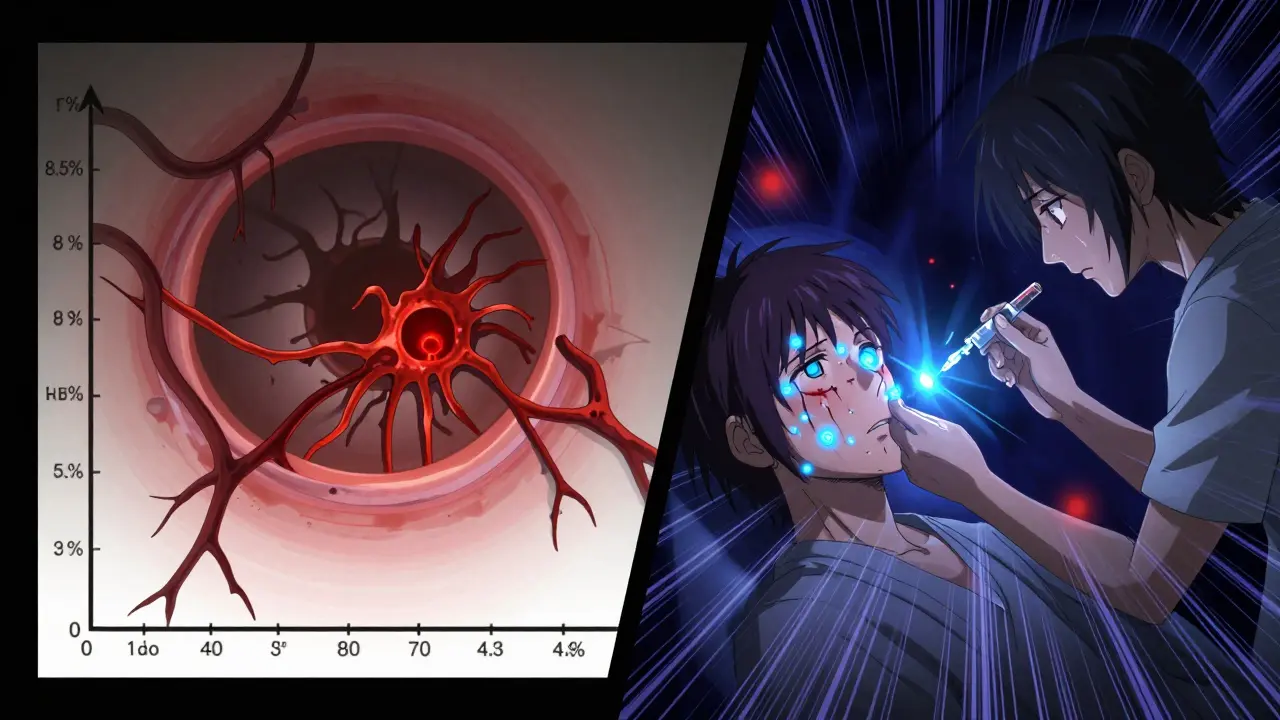

Diabetic retinopathy happens when high blood sugar damages the tiny blood vessels in the retina-the light-sensitive tissue at the back of your eye. At first, these vessels leak fluid or bleed slightly. Over time, they can close off entirely, starving parts of the retina of oxygen. In advanced stages, the eye tries to grow new blood vessels to compensate, but these are fragile, abnormal, and prone to bleeding. This can lead to scarring, retinal detachment, or glaucoma.

Diabetic macular edema (DME), a common and serious complication, occurs when fluid builds up in the macula-the part of the retina responsible for sharp central vision. About 7% of people with diabetes develop DME at some point. It doesn’t always come with symptoms early on, which is why screening is critical.

The progression isn’t the same for everyone. Someone with type 1 diabetes diagnosed at age 15 might show signs in their 20s. Someone with type 2 diabetes might have had undiagnosed high blood sugar for years before diagnosis, meaning retinopathy could already be present at the time of their diabetes diagnosis.

Screening: When and How Often?

For years, the default was an annual eye exam for every person with diabetes. But that’s changing. Research now shows that not everyone needs to be checked every year. The key is risk stratification-tailoring screening frequency based on your personal risk profile.

Here’s how current guidelines break it down:

- No retinopathy or mild nonproliferative DR: Screen every 1-2 years. If you’ve had two or more consecutive clean screenings and your HbA1c is under 7%, blood pressure is controlled, and kidney function is normal, extending screening to every 2-3 years is safe.

- Moderate nonproliferative DR: See an eye specialist within 3-6 months. This stage signals that damage is progressing and needs closer monitoring.

- Severe nonproliferative DR: Must be evaluated within 3 months. The risk of turning into proliferative retinopathy jumps significantly here.

- Proliferative DR or diabetic macular edema: Needs urgent evaluation-within 1 month. Vision loss can happen quickly without treatment.

Tools like the RetinaRisk algorithm help doctors calculate your individual risk using factors like diabetes duration, HbA1c levels, blood pressure, and kidney function. A 2023 study found this approach reduces unnecessary screenings by nearly 60% without missing any sight-threatening cases.

For type 1 diabetes, screening should start 3-5 years after diagnosis. For type 2, it should happen as soon as possible after diagnosis-because many people already have some level of retinopathy by the time they’re diagnosed.

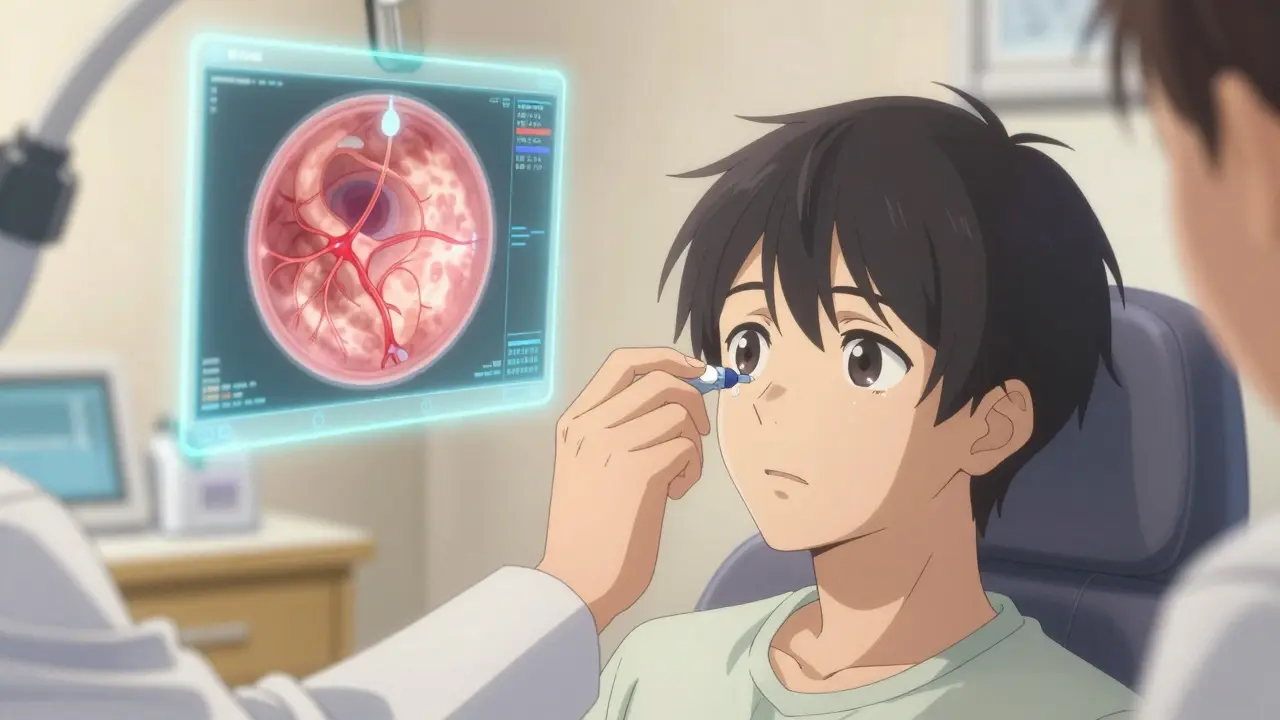

What Screening Actually Involves

Screening isn’t just a quick glance with a light. The gold standard is mydriatic digital fundus photography. That means:

- Your pupils are dilated with eye drops to get a clear view.

- Specialized cameras take high-resolution photos of the retina-usually two images per eye, covering different areas.

- These images are reviewed by trained graders using the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale, which classifies retinopathy into five levels-from no visible damage to severe proliferative disease.

Telemedicine is making this more accessible. In rural areas where eye specialists are scarce, primary care clinics can take retinal images and send them to specialists for remote review. Studies show these systems detect referable retinopathy with over 90% accuracy.

AI tools are now part of the process too. Google’s DeepMind algorithm, tested on over 11,000 retinal images, matched or exceeded human graders in spotting sight-threatening changes. The FDA-cleared IDx-DR system can even provide an automated diagnosis without a specialist present-useful in pharmacies or community health centers.

Treatment Options: From Mild to Severe

Not all diabetic retinopathy needs invasive treatment. The first line of defense is always managing the root cause: diabetes.

Controlling blood sugar and blood pressure is the most powerful tool. The DCCT/EDIC trials showed that keeping HbA1c below 7% cuts the risk of developing retinopathy by 76% in type 1 diabetes and slows progression by over half in those who already have it. Lowering systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg also significantly reduces the risk of worsening retinopathy and macular edema.

When damage has already occurred, here’s what’s used:

- Anti-VEGF injections: The most common treatment for diabetic macular edema and advanced retinopathy. Drugs like aflibercept, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab block a protein (VEGF) that causes abnormal blood vessel growth and leakage. Patients typically get injections every 4-8 weeks, then less often as the condition stabilizes. Many patients regain or stabilize vision after starting these injections.

- Laser therapy (photocoagulation): Used for proliferative retinopathy and some cases of macular edema. Focal laser seals leaking vessels; scatter laser (panretinal photocoagulation) shrinks abnormal vessels by creating small burns across the retina. It’s less common now due to anti-VEGF drugs but still effective, especially when combined with them.

- Vitrectomy: A surgical procedure for advanced cases where bleeding into the vitreous (the gel-like fluid in the eye) doesn’t clear on its own, or when scar tissue pulls the retina away. This is a last-resort option when other treatments have failed or vision is severely compromised.

There’s no one-size-fits-all. Someone with mild macular edema might only need tighter diabetes control and a follow-up in 3 months. Someone with severe proliferative retinopathy might need laser + injections + surgery over the course of a year.

Who Should Be Screened More Often?

Even with risk-stratified screening, some people need to stick with annual-or even more frequent-checkups:

- Those with HbA1c consistently above 8.5%

- People with high blood pressure (systolic over 140 mmHg)

- Anyone with kidney disease (eGFR below 60)

- Pregnant women with diabetes (retinopathy can worsen rapidly during pregnancy)

- Those with a history of rapid progression in the past

One Reddit user, 'RetinaScared2023', shared that their clinic pushed for biennial screenings despite an HbA1c of 8.5%. They developed macular edema within a year. Their story isn’t rare. Risk stratification works-but only if it’s applied correctly. If your HbA1c is high or you’ve had complications before, don’t let anyone talk you out of annual screening.

Barriers and Real-World Challenges

Even with great guidelines, access remains uneven. In the U.S., only 58-65% of people with diabetes get recommended eye exams. In rural areas, 22% of counties lack access to retinal imaging equipment. In low-income communities, rates of vision loss from diabetic retinopathy are 2.3 times higher-even though diabetes prevalence is similar.

Another issue? Inconsistent follow-up. A patient might get screened once, then forget or delay the next appointment. That’s why some clinics now use automated reminders via text or email. Others have integrated eye screening into routine diabetes visits so patients don’t have to schedule a separate trip.

Cost is also a factor. In the U.S., Medicare reimburses $45-$65 per screening. For uninsured patients, out-of-pocket costs can run $100-$200. That’s why community health centers and mobile screening units are expanding. In the UK, the National Health Service’s diabetic eye screening program covers 82% of eligible patients-and 87% of those surveyed report being satisfied with the system.

What’s Next? The Future of Screening and Treatment

Technology is making screening faster, cheaper, and more accessible. The D-Eye smartphone adapter, cleared by the FDA in 2021, lets primary care providers take retinal images with a $200 clip-on device. Studies show it matches specialist grading 89% of the time.

AI is getting smarter. New algorithms can predict not just current damage, but the likelihood of progression over the next 12-24 months. This means screening could become truly personalized-not just based on what’s visible now, but on what’s likely to happen next.

By 2030, the World Health Organization estimates that widespread adoption of risk-based screening could prevent 2.5 million cases of blindness globally. But that only happens if we fix the gaps. People in underserved areas, those without insurance, and those who don’t speak the local language still fall through the cracks.

For now, the message is simple: If you have diabetes, get your eyes checked. Don’t wait for blurry vision. Don’t assume you’re fine because you felt fine last year. And if your doctor suggests extending your screening interval, ask: Based on what? My HbA1c? My blood pressure? My kidney numbers? Make sure the decision is personalized-not just routine.

Can diabetic retinopathy be reversed?

Early damage from diabetic retinopathy can sometimes be halted or even partially reversed with tight blood sugar control and treatment like anti-VEGF injections. However, once scar tissue forms or the retina detaches, vision loss is often permanent. That’s why early detection is everything-treatment works best before irreversible damage occurs.

Do I need to get my eyes dilated every time?

Yes, for accurate screening, dilation is necessary. Non-dilated photos miss up to 30% of early retinopathy signs. Some newer cameras can capture decent images without dilation, but they’re not yet reliable enough to replace standard screening. If you’re concerned about blurry vision afterward, plan to have someone drive you home.

How often should I check my HbA1c if I have diabetic retinopathy?

If you have any level of retinopathy, aim to check your HbA1c every 3 months. Fluctuations in blood sugar-even if your average looks okay-can accelerate damage. Keeping HbA1c below 7% is the target, but even small reductions (like from 8.5% to 7.5%) make a measurable difference in slowing progression.

Can I rely on my vision to tell me if I have retinopathy?

No. Diabetic retinopathy often causes no symptoms until it’s advanced. You might see floaters, blurred vision, or dark spots-but by then, significant damage has already occurred. That’s why screening is mandatory, not optional-even if your vision feels fine.

Is laser treatment painful?

Most patients feel pressure or mild discomfort during laser treatment, but not sharp pain. Numbing drops are used, and the procedure takes less than 20 minutes. Some people report temporary blurry vision or reduced night vision afterward, but these usually improve. The trade-off-preserving central vision-is worth it for most patients.

Are there any natural remedies or supplements that help?

No supplement has been proven to prevent or treat diabetic retinopathy. While antioxidants like lutein or omega-3s are good for general eye health, they don’t replace blood sugar control or medical treatment. Be wary of claims that supplements can reverse retinopathy-they’re not backed by science.

What should I do if I miss a screening appointment?

Don’t wait until next year. Contact your eye care provider or diabetes team as soon as possible. If you’re overdue by more than 6-12 months (depending on your risk level), you may need an urgent exam. Missing one appointment doesn’t mean you’ve lost your chance-but the longer you wait, the higher the risk of irreversible damage.

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 19, 2026 AT 18:00Greg Robertson

January 20, 2026 AT 21:52Crystal August

January 22, 2026 AT 13:24Nadia Watson

January 23, 2026 AT 21:07Courtney Carra

January 25, 2026 AT 02:24clifford hoang

January 25, 2026 AT 16:01Arlene Mathison

January 25, 2026 AT 19:37Emily Leigh

January 26, 2026 AT 16:28Art Gar

January 28, 2026 AT 03:03Edith Brederode

January 29, 2026 AT 22:56Renee Stringer

January 31, 2026 AT 08:08thomas wall

February 2, 2026 AT 04:33Shane McGriff

February 3, 2026 AT 12:36Paul Barnes

February 4, 2026 AT 14:27