In Vivo vs In Vitro Bioequivalence Testing: When Each Is Used

When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a complex science designed to prove it works the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence testing comes in. It’s not just about matching ingredients-it’s about proving the drug gets into your bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the original. And there are two main ways to do it: in vivo and in vitro.

What In Vivo Bioequivalence Testing Actually Means

In vivo testing means testing inside a living body-usually humans. For most generic drugs, especially pills and capsules, this is still the gold standard. Here’s how it works: 24 healthy volunteers take the generic version and the brand-name version, one after the other, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are drawn over 24 to 72 hours to measure how much of the drug enters the bloodstream and how fast. The key numbers? Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure over time). For the drugs to be considered bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for both values must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name product.This method is sensitive. It catches differences in how the body absorbs the drug-whether it’s due to particle size, coating, or how quickly the pill breaks down in the stomach. But it’s also expensive. A single study can cost between $500,000 and $1 million. It takes months to set up-recruiting volunteers, getting ethics board approvals, running the clinical trial-and another few weeks to analyze the data. Still, for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin or levothyroxine-this is non-negotiable. Even a 5% difference in absorption could mean the difference between a seizure and a safe dose.

What In Vitro Bioequivalence Testing Actually Means

In vitro testing happens in a lab, outside a living body. Think of it as a controlled chemistry test. The most common method is dissolution testing: you put the pill in a beaker of fluid that mimics stomach or intestinal conditions, and measure how quickly the drug dissolves. Other methods include checking particle size under a microscope, measuring droplet size in inhalers, or testing how much drug comes out per spray from a nasal device.These tests are precise. Dissolution tests often have a coefficient of variation under 5%, compared to 10-20% in human studies. That means less noise, more consistency. And they’re fast-results in weeks, not months. Costs? Around $50,000 to $150,000. No human volunteers needed. No ethical hurdles. No risk of side effects.

But here’s the catch: dissolving in a beaker doesn’t always mean the same thing in your gut. Your stomach isn’t a beaker. It churns. It has enzymes. It changes pH. Food affects absorption. So, in vitro tests alone can’t always predict real-world performance. That’s why regulators only accept them in specific cases.

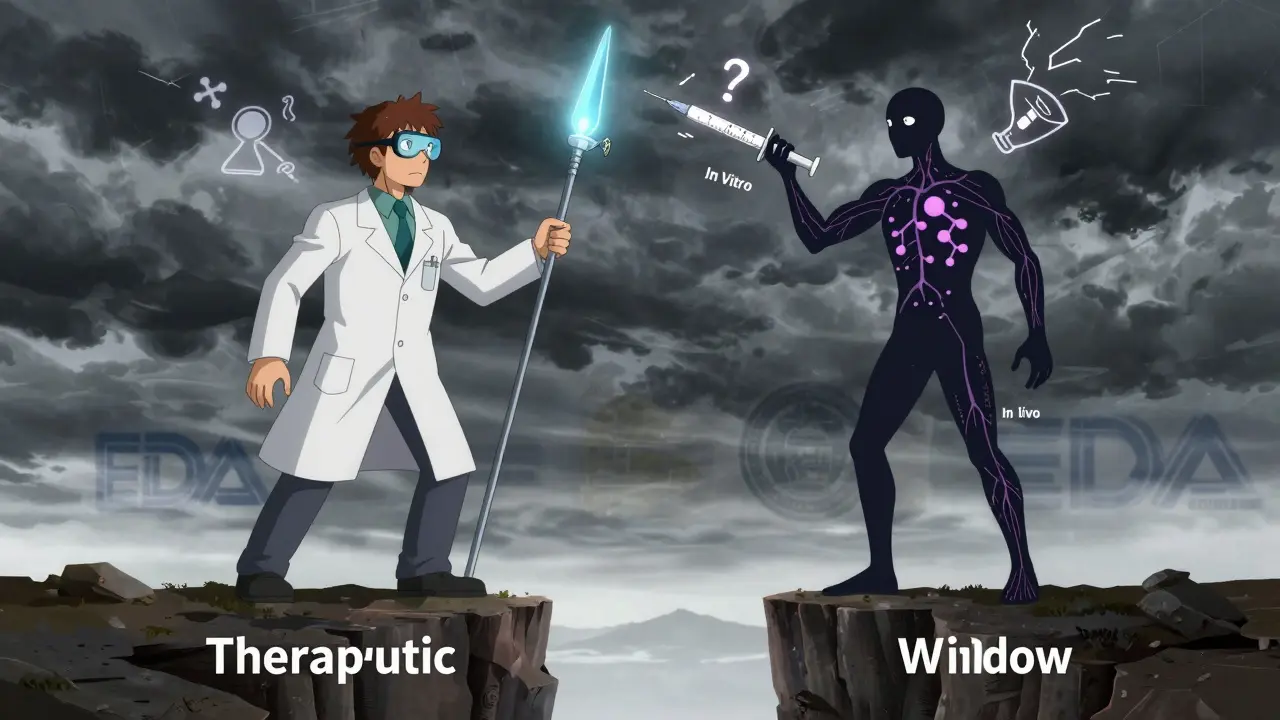

When In Vitro Testing Is Enough

The FDA and EMA now allow in vitro methods to replace human studies for certain drugs-mostly when the science is clear enough to trust the lab results.The biggest example? BCS Class I drugs. These are drugs that are both highly soluble and highly permeable-meaning they dissolve easily and get absorbed quickly, no matter the formulation. About 78% of generic applications for these drugs got biowaivers (meaning no in vivo study needed) in 2021. Think of common ones: metformin, atenolol, ranitidine. For these, dissolution testing across multiple pH levels (1.2 to 6.8) and showing 85-90% release within 30 minutes is often enough to prove equivalence.

Another major area: inhalers and nasal sprays. Testing these in humans is messy. How do you control how deeply someone inhales? How much of the dose even reaches the lungs? In vitro methods like cascade impactors (which measure particle size distribution) and dose uniformity tests are now accepted as primary evidence. In fact, Teva’s generic budesonide nasal spray got FDA approval in October 2022 based solely on in vitro data-a landmark moment.

Topical products like antifungal creams or steroid lotions also often rely on in vitro testing. Why? Because the drug isn’t meant to enter your bloodstream-it’s meant to work on your skin. Systemic exposure doesn’t matter. What matters is whether the cream delivers the right amount of drug to the surface. Dissolution, spreadability, and particle size tests can prove that.

When In Vivo Testing Is Still Required

Not all drugs can be trusted to a beaker. Here’s when human testing still wins:- Narrow therapeutic index drugs: Warfarin, digoxin, lithium. These have tiny safety margins. A small difference in absorption could be dangerous. The FDA requires tighter limits: 90-111.11% for Cmax and AUC.

- Drugs affected by food: If a pill works better with a meal, you have to test it both fasting and fed. In vitro can’t simulate what you ate for breakfast.

- Drugs with nonlinear pharmacokinetics: When higher doses don’t lead to proportional increases in blood levels, human studies are needed to map the curve.

- Modified-release products: Extended-release pills that release drug over 12 or 24 hours are hard to model in a beaker. The release profile must be matched exactly, and in vivo data still provides the best validation.

- When IVIVC isn’t established: In vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is a mathematical model that links lab dissolution data to actual human absorption. Only when this model has a strong correlation (r² > 0.95) can regulators trust in vitro results. That’s rare outside BCS Class I drugs.

A 2018 study in the AAPS Journal found that in vitro tests correctly predicted bioequivalence for 92% of BCS Class I drugs-but only 65% of BCS Class III drugs (low solubility, high permeability). That gap shows why you can’t apply one rule to all drugs.

Real-World Trade-Offs: Cost, Time, and Risk

Let’s talk numbers. A typical in vivo bioequivalence study takes 4-6 months from start to finish. You need a certified clinical unit, trained staff, electronic data systems compliant with FDA regulations, and 24 healthy volunteers who can commit to multiple visits. The total cost? $500,000-$1 million. Documentation? 300-500 pages of raw data, statistical analysis, and subject reports.An in vitro study? You can run it in 2-4 weeks. Cost? $50,000-$150,000. Documentation? 50-100 pages. But here’s the hidden cost: method development. Building a reliable dissolution test for a new drug can take 3-12 months. You need specialized equipment-like USP Apparatus 4 flow-through cells, which cost $85,000-$120,000 each. And you need scientists who understand biopharmaceutics, not just chemistry.

Industry professionals have mixed experiences. One formulation scientist from Teva said switching to in vitro testing saved $1.2 million and 8 months for a BCS Class I drug-but it took 3 months of extra work to get the method approved. Another manager from Viatris said their topical antifungal, approved via in vitro testing, later needed an in vivo study after patient reports of reduced effectiveness. That cost $850,000 and delayed market entry by 11 months.

The Future: Hybrid Models and Regulatory Shifts

The field is moving. The FDA’s 2023 White Paper on Modernizing Bioequivalence Determinations envisions a future where in vitro testing, backed by advanced modeling, becomes the default for most drugs. In silico tools like physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling are already being used to predict absorption based on drug properties and gut physiology.Regulators are catching up. The EMA approved 214 biowaivers based on in vitro data in 2022-up 27% from 2020. The FDA’s GDUFA IV plan (2023-2027) commits to issuing two new guidances on in vitro testing for complex products by December 2025. The goal? Reduce reliance on human testing without compromising safety.

But the shift isn’t universal. For nasal sprays, the FDA still requires both in vitro and in vivo data in 63% of cases. For narrow therapeutic index drugs, human studies remain mandatory. The science isn’t there yet.

What’s clear is this: the future isn’t in vivo or in vitro. It’s in vivo and in vitro-used together where needed. In vitro for screening, optimization, and routine quality control. In vivo for validation, especially when risk is high.

Bottom Line: Which One Should You Trust?

If you’re a patient: you don’t need to know the method. You just need to know the generic drug is approved by the FDA or EMA. Both methods are scientifically valid when applied correctly.If you’re a manufacturer: choose in vitro if you’re working with a BCS Class I drug, an inhaler, or a topical product. It’s faster, cheaper, and less risky. But if you’re dealing with a narrow therapeutic index drug, a food-effect issue, or a modified-release formulation-don’t skip the human study. The cost of failure is too high.

If you’re a regulator or researcher: keep pushing for better in vitro models. Invest in IVIVC, PBPK, and physiologically relevant dissolution systems. The goal isn’t to replace human testing entirely-it’s to replace it only when you can prove you’re not missing anything critical.

At the end of the day, bioequivalence isn’t about which method is better. It’s about using the right tool for the right drug. And that’s what keeps generic drugs safe, effective, and affordable.

Danielle Stewart

December 20, 2025 AT 06:26Really appreciate this breakdown. I work in pharmacy and seeing how they validate generics makes me feel way better about prescribing them. The math behind Cmax and AUC is wild but so elegant.

shivam seo

December 20, 2025 AT 18:41Wow another corporate shill post. In vitro? Please. Big Pharma just wants to cut costs and poison people faster. Remember Vioxx? They skipped human trials then too.

Andrew Kelly

December 21, 2025 AT 03:58Let me guess-this is why your blood pressure med doesn’t work anymore. They swapped out the filler for cornstarch and now you’re having panic attacks. They’re not testing for *your* metabolism, just the average Joe in a clinical trial.

Anna Sedervay

December 22, 2025 AT 13:43While I appreciate the technical rigor, I must point out that the very notion of 'bioequivalence' is a capitalist construct designed to commodify human physiology. Who defines 'equivalence'? A committee funded by the same corporations that profit from the generics? This is epistemological violence disguised as science.

Ashley Bliss

December 24, 2025 AT 05:43It’s not just about the drug-it’s about the soul. When you swallow a pill that was never tested on a real human body, aren’t you swallowing a piece of the system’s indifference? I mean, think about it-your body is a temple, and they’re just running dissolution tests like it’s a factory line. Where’s the reverence? Where’s the humanity?

Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 25, 2025 AT 04:57Great summary! For BCS Class I drugs, in vitro is totally reliable-I’ve seen it in my lab work. Just make sure the dissolution profile matches across pH 1.2 to 6.8 and you’re golden. Also, don’t forget to check particle size distribution. Small things matter.

Mahammad Muradov

December 25, 2025 AT 10:59Anyone who thinks in vitro is sufficient for anything beyond aspirin is delusional. The human gut is not a beaker. You can’t simulate bile salts, microbiome activity, or gastric motility in a lab. This is why so many generics fail in real life. The regulators are lazy.

holly Sinclair

December 26, 2025 AT 16:10What does ‘equivalence’ even mean when we’re talking about living systems? If two drugs produce the same AUC but one causes subtle epigenetic changes the other doesn’t, are they still equivalent? Or are we just measuring what’s convenient to measure? The reductionism here is breathtaking. We’ve turned the human body into a spreadsheet. And we call it progress.

Monte Pareek

December 27, 2025 AT 05:58Let me tell you something straight up. In vitro saves lives by getting life-saving meds to people who can’t afford the brand. That’s not corporate greed-that’s justice. Yeah, it takes time to build a good dissolution method. But once you do, you’re not just saving money-you’re saving families. I’ve seen kids in rural India get their asthma meds because we cut the cost by 90%. Don’t hate the tool. Hate the system that makes it necessary.

Tim Goodfellow

December 27, 2025 AT 21:30Man, this is the kind of stuff that makes me love science. Dissolution profiles like a symphony, PBPK models like a weather forecast for your bloodstream. The future’s not just in vitro or in vivo-it’s a hybrid orchestra. And someone’s finally tuning the damn instruments.

Edington Renwick

December 29, 2025 AT 00:45You people are naive. They’re using in vitro to hide bad formulations. That Teva nasal spray? Patients are reporting zero effect. They didn’t test for mucosal adhesion. They just measured particle size. And now people are suffering. This isn’t innovation-it’s negligence dressed up as efficiency.