Lipoprotein(a): Understanding Your Genetic Cholesterol Risk and What You Can Do

Most people know about LDL cholesterol - the so-called "bad" cholesterol - and how it contributes to heart disease. But there’s another cholesterol-related particle hiding in plain sight, one that doesn’t show up on routine blood tests and isn’t affected by diet or exercise: lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). If you’ve had a heart attack before 50, or if heart disease runs in your family, Lp(a) might be the hidden reason why.

What Exactly Is Lipoprotein(a)?

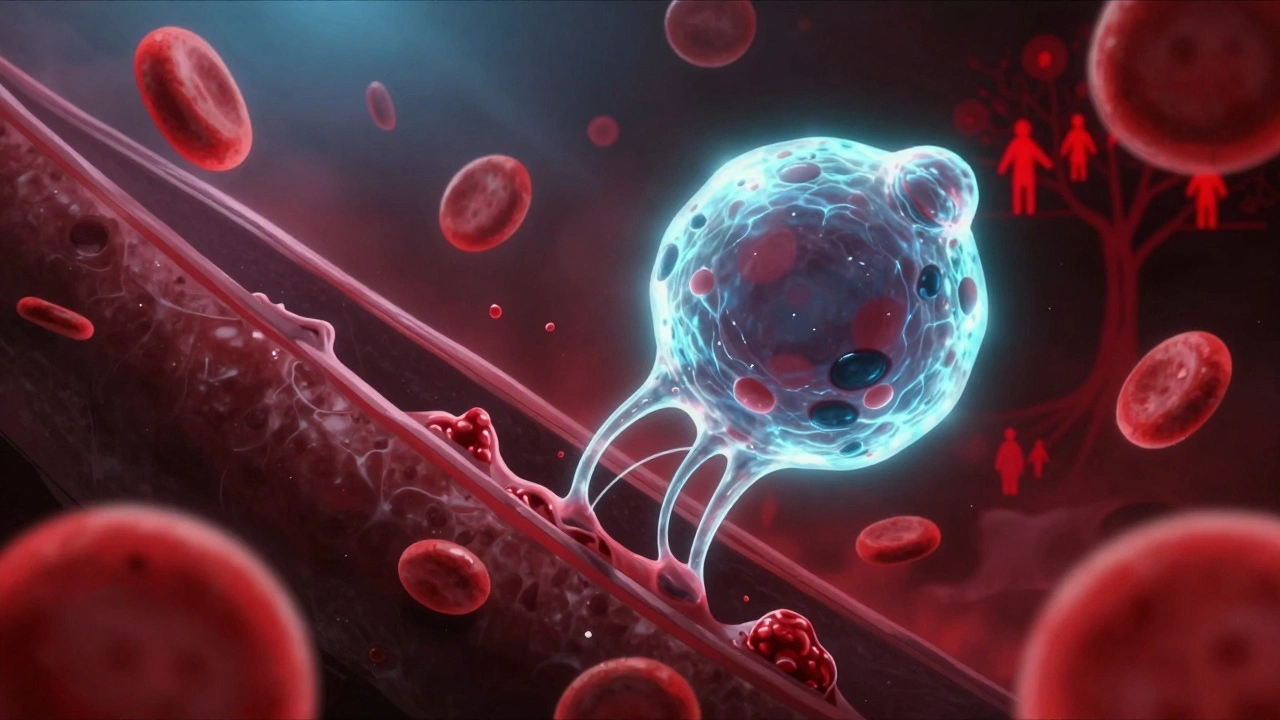

Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), is a type of cholesterol-carrying particle in your blood. Think of it like LDL cholesterol - the kind that builds up in your arteries - but with a strange extra protein attached: apolipoprotein(a). This protein has a unique structure made of repeating segments called kringle domains. These aren’t just decorative. They make Lp(a) sticky, allowing it to cling to damaged areas in artery walls and interfere with your body’s natural ability to break down blood clots.

Unlike regular LDL, Lp(a) levels are mostly set at birth. About 70% to 90% of your Lp(a) level comes from your genes - specifically, variations in the LPA gene. This gene controls how many kringle repeats you have, and that number determines how much Lp(a) your liver makes. The more repeats, the lower your Lp(a); fewer repeats mean higher levels. It’s one of the most genetically determined risk factors for heart disease in humans.

And here’s the kicker: if one of your parents has high Lp(a), you have a 50% chance of inheriting it. It doesn’t skip generations. It doesn’t care if you’re fit or eat kale. If your genes say you have high Lp(a), you do - no matter what you do.

Why It’s Dangerous

Lp(a) doesn’t just add to your cholesterol burden - it actively harms your arteries in multiple ways. First, it delivers cholesterol to artery walls, helping form plaques. Second, it triggers inflammation inside those plaques, making them more likely to rupture and cause a heart attack or stroke. Third, because of its kringle structure, it binds to fibrin, a key protein in blood clots, and blocks the body’s natural clot-busting system. This means clots last longer and grow bigger.

The result? Higher Lp(a) levels are linked to:

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attacks, even in people with otherwise normal cholesterol

- Stroke

- Peripheral artery disease

- Aortic valve stenosis - a condition where the heart’s main valve narrows

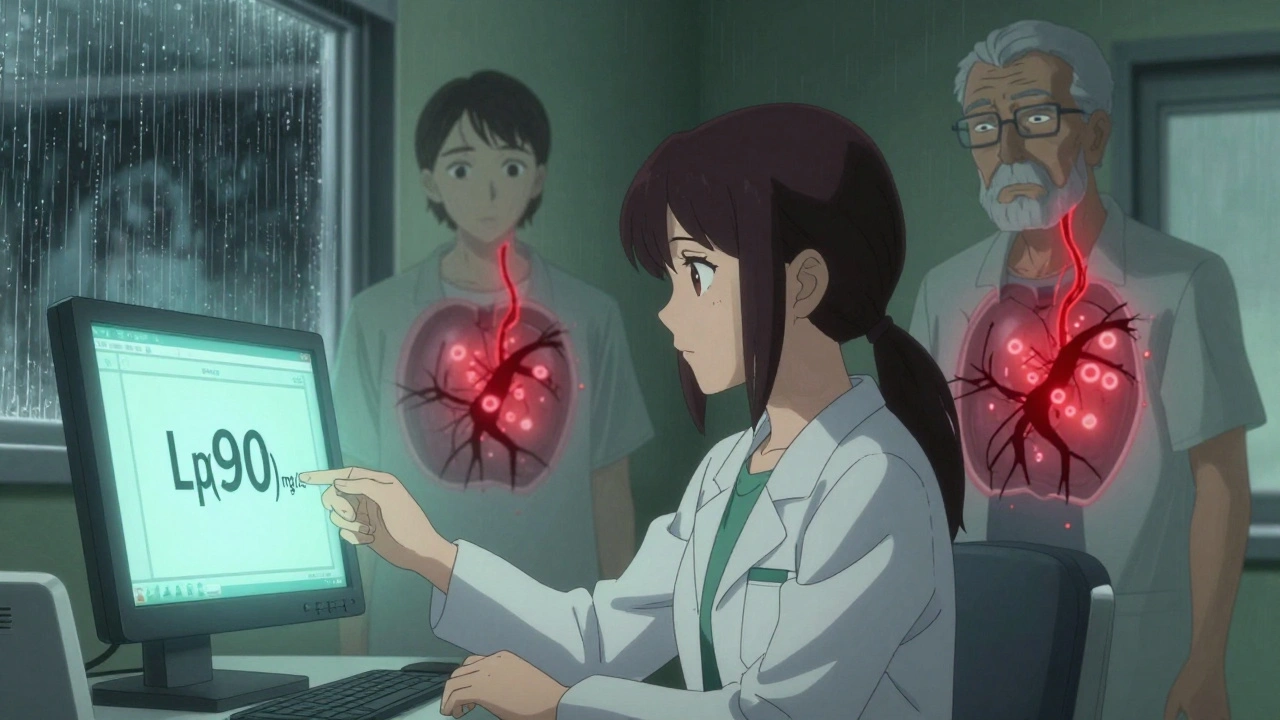

Studies show that people with Lp(a) levels above 50 mg/dL (or 105 nmol/L) have a risk of heart attack or stroke similar to someone with familial hypercholesterolemia - a well-known genetic disorder that causes extremely high LDL. Some people have levels above 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L), putting them at risk equal to someone who already had a heart attack.

Who Should Be Tested?

Lp(a) isn’t part of a standard lipid panel. Your doctor has to specifically order it. That’s why so many people - including those who’ve had early heart attacks - never find out they have it.

Experts now recommend testing for Lp(a) in people with:

- A family history of early heart disease (before age 55 in men, before age 65 in women)

- A personal history of heart attack, stroke, or aortic stenosis without obvious causes like smoking or diabetes

- Familial hypercholesterolemia

- Unexplained high cholesterol despite lifestyle changes and statins

- Black ancestry - Black individuals, on average, have higher Lp(a) levels than other groups

Women should also consider testing around menopause. Estrogen suppresses Lp(a), so when estrogen drops after menopause, Lp(a) levels often rise. That’s one reason why heart disease risk increases sharply in women after 50.

One in five people worldwide - about 20% - have elevated Lp(a). That makes it the most common genetic cause of high cholesterol-related heart disease.

Can You Lower It?

This is the hardest part: you can’t lower Lp(a) with diet, exercise, or weight loss. No matter how clean your eating or how hard you train, your Lp(a) level won’t budge much - if at all.

Statins, the most common cholesterol drugs, don’t help. In fact, they can sometimes raise Lp(a) slightly. Niacin (vitamin B3) can reduce Lp(a) by 20-30%, but it causes serious side effects like flushing, liver damage, and increased blood sugar. It’s rarely used anymore.

So what’s the point of knowing your Lp(a) if you can’t change it?

Here’s the answer: you can still lower your overall risk. If you have high Lp(a), you need to aggressively manage every other risk factor you can control.

- Keep LDL cholesterol as low as possible - often below 70 mg/dL, sometimes even lower

- Treat high blood pressure

- Don’t smoke

- Manage diabetes if you have it

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Get enough sleep and reduce stress

For people with very high Lp(a) and existing heart disease, doctors may prescribe PCSK9 inhibitors (like evolocumab or alirocumab). These injectable drugs can lower Lp(a) by 20-30% - not as much as you’d want, but enough to help reduce overall risk.

The Future: New Drugs on the Horizon

The most exciting development in Lp(a) treatment is a new class of drugs called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). One of them, called pelacarsen, has shown in early trials that it can slash Lp(a) levels by up to 80%.

The big phase 3 trial - called Lp(a) HORIZON - is currently testing whether lowering Lp(a) with pelacarsen actually prevents heart attacks, strokes, and death in high-risk patients. The trial includes people with Lp(a) levels above 430 nmol/L (90 mg/dL) and known heart disease. Results are expected in 2025.

If the trial works, pelacarsen could become the first treatment specifically approved to target Lp(a). That would change everything. Instead of just managing risk, we’d be directly attacking the root cause.

Other drugs are also in development, including RNA-based therapies that silence the LPA gene. These aren’t just band-aids - they’re potential cures for a genetic problem.

What You Should Do Now

Even without a cure, knowing your Lp(a) level gives you power. If you’ve had unexplained heart disease, or if your family has a history of early heart attacks, ask your doctor for an Lp(a) test. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume your cholesterol is fine because your LDL is low.

If your level is high:

- Work with your doctor to get your LDL as low as possible - statins, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitors may be needed

- Monitor your blood pressure and blood sugar closely

- Get regular check-ups - annual ECGs or coronary calcium scans might be recommended

- Inform your close relatives - they should be tested too

And if you’re healthy but have a family history? Get tested. Prevention is always better than treatment.

Lp(a) isn’t your fault. It’s not because you ate too much butter or didn’t run enough miles. It’s genetics. But now, for the first time, science is catching up. In the next few years, we may have tools to fight back - not just manage the damage.

Is Lp(a) the same as LDL cholesterol?

No. Lp(a) is a separate particle that contains an LDL-like core but has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached. While both carry cholesterol, Lp(a) is genetically determined and much harder to lower. It also promotes blood clotting and inflammation in ways LDL doesn’t.

Can lifestyle changes lower Lp(a)?

Not meaningfully. Diet, exercise, and weight loss have little to no effect on Lp(a) levels. While healthy habits are still important for overall heart health, they won’t reduce your Lp(a) number. That’s why testing is critical - it tells you when you need stronger medical intervention.

How often should I get tested for Lp(a)?

Once is usually enough. Since Lp(a) is genetically determined, your level doesn’t change much over time. A single test, ideally done in adulthood, is sufficient unless you have a rare condition like kidney disease that might affect it. Repeat testing is only needed if your doctor suspects a secondary cause.

If my Lp(a) is high, do I need to take medication?

Not necessarily because of Lp(a) alone. But if your Lp(a) is high and you have other risk factors - like high LDL, high blood pressure, or a family history of early heart disease - your doctor will likely recommend aggressive treatment of those other factors. This may include statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, or other medications to lower your overall risk.

Are there any natural supplements that lower Lp(a)?

No reliable evidence supports any supplement for lowering Lp(a). Some people claim niacin, fish oil, or vitamin C help, but studies show inconsistent or minimal effects. Niacin can reduce Lp(a) slightly but comes with serious side effects. Don’t waste money on unproven supplements - focus on proven medical strategies instead.

Ada Maklagina

December 5, 2025 AT 08:16Lp(a) is just another thing doctors use to scare you into more tests

My grandma lived to 92 eating bacon and never saw a lipid panel

Norene Fulwiler

December 6, 2025 AT 20:37I’m a Black woman with a dad who had a heart attack at 48. I got tested last year - Lp(a) was 120. No one ever told me to ask. I’m pissed. But now I’m on a high-dose statin, ezetimibe, and I’m pushing for a PCSK9. Knowledge is power, but someone had to hand me the key. Don’t wait like I did.

Michael Dioso

December 8, 2025 AT 11:28So let me get this straight - your genes screw you over, but you’re supposed to take expensive injections to fix what you can’t control?

That’s not medicine. That’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Juliet Morgan

December 10, 2025 AT 10:59My sister’s Lp(a) was through the roof. She didn’t even know it existed until after her stroke. Now she’s on PCSK9 and doing way better. If you’ve got family history - just get tested. It’s one blood draw. It could save your life. I’m not saying it’s easy, but it’s worth it.

William Chin

December 11, 2025 AT 16:55It is imperative to underscore that Lp(a) is not a modifiable risk factor, and therefore, the clinical imperative lies in the aggressive management of concomitant atherogenic variables. Failure to do so constitutes a dereliction of duty in preventive cardiology.

Furthermore, the absence of routine screening protocols constitutes a systemic failure in public health infrastructure.

Philip Kristy Wijaya

December 13, 2025 AT 07:35So you’re telling me I’m doomed because my dad had a heart attack and I inherited some protein that makes my blood sticky

Meanwhile I’ve been eating tofu and running marathons for ten years

Thanks for the reassurance doctor

Maybe I should just quit and eat ice cream

Katie Allan

December 14, 2025 AT 01:00What strikes me most is how genetics can isolate us - we’re told our risk is fixed, so we stop feeling in control. But the real power isn’t in changing Lp(a). It’s in choosing not to add more weight to the burden. Lowering LDL, quitting smoking, managing stress - those aren’t just backups. They’re acts of radical self-respect. You’re not powerless. You’re just being asked to fight smarter.

Harry Nguyen

December 14, 2025 AT 01:24They want you to believe your genes are your destiny

But what if this is just a scam to sell more drugs

Who profits when you panic about a number you can’t change

Big Pharma doesn’t care if you live

They care if you keep buying

sean whitfield

December 14, 2025 AT 07:33So I got my Lp(a) tested. 140. My doctor says take statins. I said no. I take vitamin D and laugh at cholesterol charts. If God wanted me to have low Lp(a) he wouldn’t have given me a liver. Let the pills do their thing. I’ll be over here eating cheese and ignoring the future.