MRSA Infections: How Community and Hospital Strains Differ in Spread and Treatment

MRSA isn’t just one bug. It’s two very different ones wearing the same name. You might hear "MRSA" and think of a hospital-acquired infection - something that happens to someone after surgery or a long stay in a nursing home. But today, you’re just as likely to catch it from your kid’s wrestling team, your gym locker, or even a shared needle. The line between what’s "hospital MRSA" and what’s "community MRSA" is fading fast, and that’s changing how doctors treat it - and how we all protect ourselves.

What MRSA Really Is

MRSA stands for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It’s a type of staph bacteria that doesn’t respond to common antibiotics like methicillin, penicillin, or amoxicillin. Staph is everywhere - on skin, in noses, in the air. Most of the time, it’s harmless. But when it gets into a cut, a burn, or a surgical wound, it can turn dangerous. And when it’s MRSA, your usual antibiotics won’t touch it.

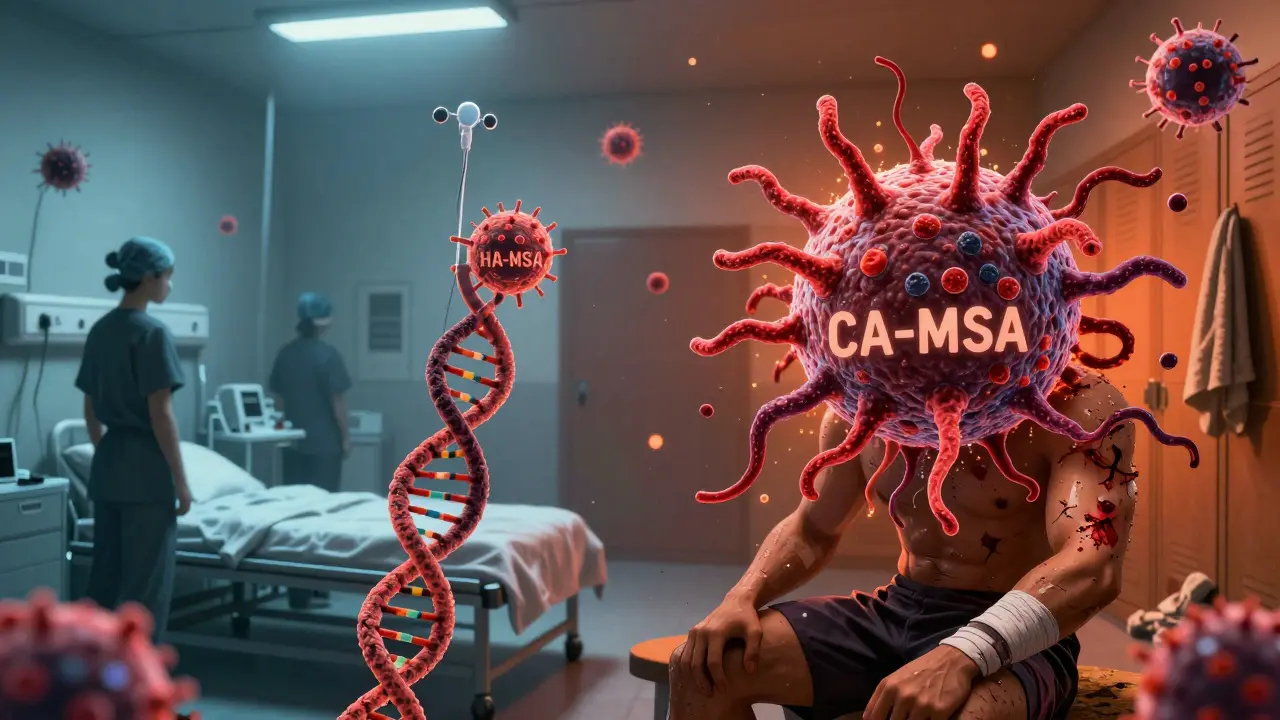

There are two main types: one that started in hospitals (HA-MRSA), and one that exploded in the community (CA-MRSA). They’re not just different in where they’re found - they’re genetically different, behave differently, and need different treatments.

HA-MRSA: The Hospital-Bred Threat

HA-MRSA has been around since the 1960s, right after methicillin was introduced. It thrives in hospitals because it’s built for that environment. These strains carry large chunks of DNA called SCCmec types I, II, or III. That means they’re resistant to not just one or two antibiotics, but often six, seven, or more. In fact, over 90% of HA-MRSA strains are resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones.

People who get HA-MRSA are usually already sick. They’ve had surgery, are on dialysis, have a catheter, or have been in a hospital or nursing home for weeks. The infection often shows up as a bloodstream infection, pneumonia, or a surgical site infection. Treatment is tough - doctors have to use last-resort drugs like vancomycin or linezolid. Hospital stays are long - the average is over three weeks. And once someone gets HA-MRSA, they can carry it for months, even years, without symptoms, quietly spreading it to others.

CA-MRSA: The Community Invader

CA-MRSA didn’t show up until the late 1990s. Suddenly, healthy teenagers, athletes, and moms with kids in daycare were getting painful, red, swollen boils that looked like spider bites. These weren’t hospital patients. They had no recent medical history. And they were getting sick fast.

What made CA-MRSA different? Smaller DNA chunks - SCCmec types IV and V. That means less resistance to antibiotics, but way more power to hurt you. Many CA-MRSA strains make a toxin called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). This toxin kills white blood cells, turning a simple skin infection into a necrotizing wound or even a deadly lung infection.

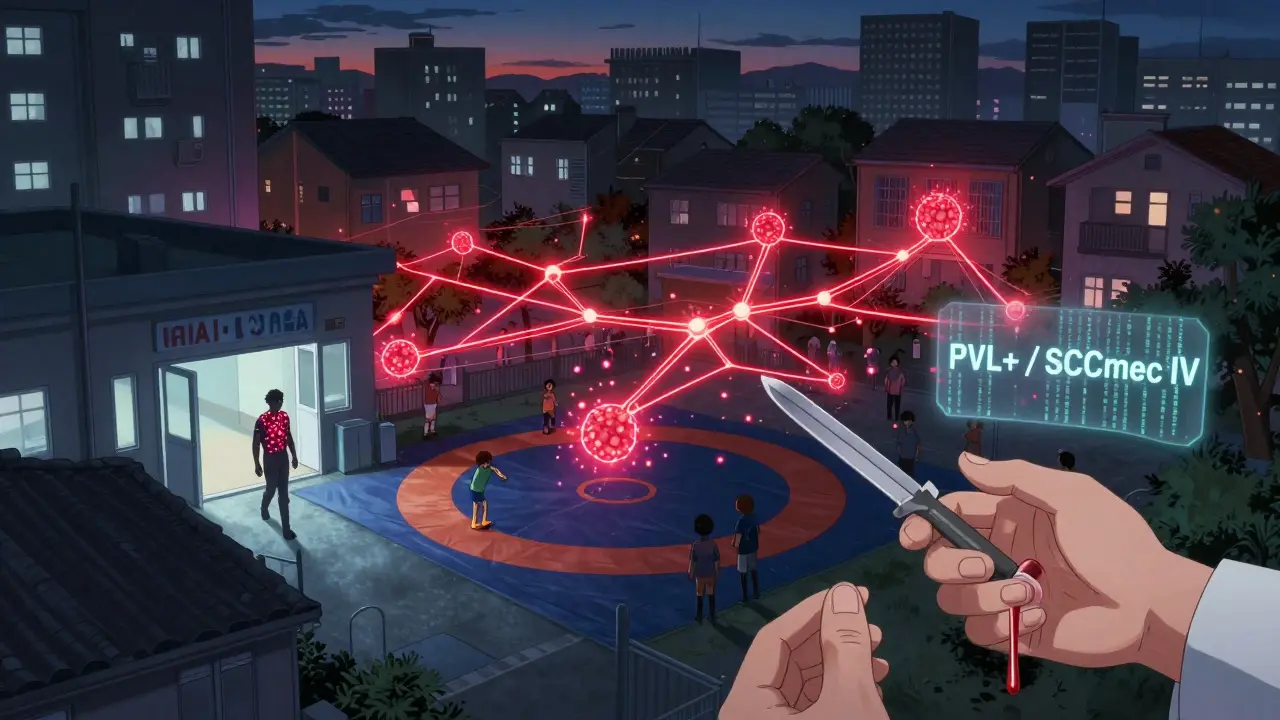

The USA300 strain is the biggest player in the U.S., making up about 70% of all CA-MRSA cases. It’s the reason you hear about MRSA outbreaks in prisons, military barracks, and homeless shelters. The risk is 15 times higher in prisons. It’s also common among people who inject drugs - needle sharing, dirty skin, and poor hygiene make it easy to spread.

Transmission: How It Moves Between Worlds

Here’s the scary part: MRSA doesn’t stay in its lane. People move between hospitals and communities every day. A nurse who carries CA-MRSA on their skin might bring it into a hospital. A patient discharged with HA-MRSA might take it home to their family.

Studies show that nearly 30% of MRSA infections that start in hospitals are actually caused by community strains. And 30% of community infections come from hospital strains. That’s not a glitch - it’s the new normal. The average hospital stay is 4 to 5 days. But MRSA can live on your skin for hundreds of days. So someone walks out of the hospital carrying HA-MRSA, goes to the gym, shares a towel, and infects someone who’s never set foot in a hospital.

It’s not just skin-to-skin contact. It’s towels, razors, gym equipment, bedding, and even shared phones. In crowded places - shelters, dorms, locker rooms - transmission is easy. And because CA-MRSA spreads faster and causes more visible infections, it’s often noticed before HA-MRSA, which can silently build up in a ward.

Treatment: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

For a small skin abscess caused by CA-MRSA? Often, you don’t need antibiotics at all. Just drain it. Cut it open, clean it out, and let it heal. That’s it. But if you do need medicine, clindamycin works in 96% of CA-MRSA cases. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and tetracyclines are also good options.

HA-MRSA? Not so simple. Because it’s resistant to so many drugs, doctors have to use stronger ones. Vancomycin, daptomycin, or linezolid are common. But these drugs are harder on the body, more expensive, and often need to be given through an IV. And if the strain has picked up resistance to those too? You’re in trouble.

The real problem now? Hybrid strains. Some CA-MRSA is picking up HA-MRSA’s resistance genes. Some HA-MRSA is picking up CA-MRSA’s PVL toxin. These new versions are harder to predict, harder to treat, and harder to track. A patient might come in with a skin infection, and the doctor assumes it’s CA-MRSA - so they prescribe clindamycin. But if it’s a hybrid strain, the antibiotic fails. The infection spreads. And now it’s worse.

Why the Old Definitions Are Broken

The CDC used to define CA-MRSA as an infection in someone with no recent hospital contact. That made sense back in 2005. But today? That definition is useless. A person might have had a minor surgery six months ago. Or visited a relative in a nursing home. Or been in the ER for a broken arm. That’s enough to pick up HA-MRSA - but they’re still a "community patient." Meanwhile, someone with no hospital history could have a CA-MRSA strain that’s now resistant to clindamycin because it’s evolved.

Doctors can’t rely on history anymore. They have to rely on the bug itself. Labs now do genetic testing to find out if it’s USA300, ST59, or another strain. That tells them more about how to treat it than whether the patient was in a hospital last month.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

You can’t avoid MRSA entirely - but you can cut your risk.

- Wash your hands often - especially after the gym, after touching wounds, or before eating.

- Don’t share towels, razors, or sports gear.

- Cover cuts and scrapes with clean bandages until they heal.

- Shower immediately after contact sports.

- If you’re in a hospital, ask staff to wash their hands before touching you.

- If you have a skin infection that’s red, hot, swollen, or oozing - don’t ignore it. See a doctor. Don’t try to pop it yourself.

And if you’ve had MRSA before? Tell your doctor. Even if it was years ago. That changes how they treat you next time.

The Future: One System, Not Two

We’re moving past the idea that MRSA is either "hospital" or "community." It’s one big, messy, interconnected system. Strains move between them. Resistance genes jump around. Toxin genes spread. Surveillance needs to track that whole system - not just hospital records or community clinics.

Some places are already adapting. Hospitals now screen high-risk patients for MRSA on admission. Some clinics test skin infections for PVL toxin. Public health departments are tracking MRSA strains across entire cities, not just hospitals.

But the biggest change? Doctors are learning to treat the bug, not the label. If you have a skin infection, they’re not asking, "Were you in the hospital?" They’re asking, "What does the culture say?" And that’s the right question.

MRSA didn’t disappear. It just got smarter. And so do we.

Can you get MRSA from a toilet seat?

It’s possible, but unlikely. MRSA spreads mostly through direct skin contact or touching contaminated surfaces like towels, gym equipment, or shared razors. Toilets aren’t a major source unless they’re visibly dirty and you have an open wound. Good handwashing after using the bathroom is more important than avoiding the seat.

Is MRSA always dangerous?

No. Many people carry MRSA on their skin or in their nose without ever getting sick. That’s called colonization. It only becomes dangerous if the bacteria enter the body through a cut, burn, or medical device. Most community cases are just skin infections - painful, but treatable. The real danger comes when it spreads to the bloodstream, lungs, or bones.

Can you cure MRSA completely?

Yes, most people clear MRSA infections with proper treatment. Skin infections often resolve with drainage and antibiotics. But clearing the bacteria from your nose or skin entirely is harder. Some people remain colonized for months or years, even after the infection is gone. That doesn’t mean they’re sick - just that they can still spread it. Decolonization treatments (like nasal ointment and body washes) can help, but they’re not always permanent.

Are antibiotics the only treatment for MRSA?

No. For many skin infections, especially those caused by CA-MRSA, draining the abscess is the most effective treatment - often better than antibiotics. Antibiotics are used when the infection is deeper, spreading, or in someone with a weakened immune system. Overusing antibiotics can make MRSA worse by encouraging resistance.

Why is CA-MRSA spreading so fast in the community?

CA-MRSA strains are more contagious because they’re more aggressive. They produce toxins that damage tissue and help the bacteria spread. They also don’t carry as many resistance genes, so they grow faster and compete better in environments with less antibiotic pressure - like homes, gyms, and schools. Plus, they spread easily in crowded, close-contact settings where hygiene is poor.

Can you get MRSA from pets?

Yes, but it’s rare. Pets - especially dogs and cats - can carry MRSA, usually picked up from their human owners. If your pet has a skin infection, or you’ve been in close contact with someone who has MRSA, it’s possible to pass it back and forth. Always wash your hands after handling a pet with a wound, and don’t let pets lick open cuts.

Adam Rivera

January 13, 2026 AT 09:35Man, I never thought about MRSA being two different beasts. I thought it was just "super staph." But now I get why my cousin’s boil cleared up with just a drain and no antibiotics, while my uncle needed a week in the hospital with IV drugs. This is wild stuff.

Also, never sharing towels again. Ever. I’m guilty of borrowing my gym buddy’s towel after a sweat session. Not anymore.

Rosalee Vanness

January 13, 2026 AT 11:37As someone who works in pediatrics, I’ve seen CA-MRSA turn a simple scratch into a full-blown abscess in under 48 hours. The PVL toxin? It’s like the bacteria has a vendetta against white blood cells. I’ve had parents cry because they thought it was a spider bite - until the culture came back.

And yes, showering after wrestling practice isn’t just for hygiene - it’s a lifeline. Kids don’t realize how much skin-to-skin contact happens in those mats. We’re not just teaching them technique - we’re teaching them survival.

mike swinchoski

January 13, 2026 AT 18:05People are so lazy these days. Wash your hands. Cover your cuts. Don’t be a germ factory. It’s not rocket science. If you’re getting MRSA from a gym locker, you’re doing life wrong. No excuses. Stop blaming the bacteria - blame yourself.

Trevor Whipple

January 15, 2026 AT 09:13ok so i just read this and my mind is blown. i had a staph infection last year and they gave me sulfa pills and it went away. but now im worried i had CA-MRSA and never knew it. also, can you get it from your dog licking your face? my dog does that. and i dont wash my face after. 🤔

John Pope

January 16, 2026 AT 21:12Let’s be honest - the entire medical paradigm is broken. We’re still clinging to binary labels like "hospital" and "community" like it’s 2007. But MRSA doesn’t care about your insurance provider or your last hospital discharge date. It’s a Darwinian winner - evolving, hybridizing, outsmarting our diagnostic tools.

The real crisis isn’t the infection - it’s our refusal to treat it as a dynamic, adaptive organism. We’re still using paper charts and outdated definitions while the bacteria is writing its own genome in real time. We need genomic surveillance at the population level - not just in ICU wards.

James Castner

January 18, 2026 AT 06:29While the distinction between HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA is indeed becoming blurred, we must not lose sight of the fundamental epidemiological truth: transmission dynamics are shaped by human behavior, not merely bacterial genetics. The notion that MRSA is "one big, messy, interconnected system" is not a revelation - it is a logical consequence of globalization, urban density, and the erosion of public health infrastructure.

Consider this: the very same socioeconomic factors that drive overcrowded prisons, undocumented labor migration, and under-resourced clinics are the same forces that allow CA-MRSA to propagate with alarming efficiency. The PVL toxin is not the villain - it is merely the molecular manifestation of systemic neglect. We treat the bug, yes - but we must also treat the conditions that birth it.

Moreover, the overreliance on vancomycin and linezolid reflects a deeper failure in antimicrobial stewardship. We deploy these last-resort agents as first-line solutions because our diagnostic pipelines are slow, fragmented, and underfunded. We need rapid point-of-care genomic sequencing in every ER - not just academic medical centers.

And while handwashing is important, it is not a panacea. We must confront the institutional failure to provide soap, running water, and disposable towels in homeless shelters, correctional facilities, and rural clinics. The bacteria thrives where dignity is absent.

Let us not mistake individual hygiene for collective responsibility. The real question is not whether we can cure MRSA - but whether we are willing to dismantle the structures that allow it to flourish.

lucy cooke

January 19, 2026 AT 01:44Oh, darling, this is just the latest chapter in the tragic opera of human hubris. We invented antibiotics as our gods, then we worshipped them - and now, like Icarus, we’ve melted our wings. MRSA isn’t a bug. It’s a moral allegory.

HA-MRSA? The aristocrat of pathogens - refined, cultured, resistant to everything but dignity.

CA-MRSA? The punk rock rebel - raw, rebellious, dripping with PVL toxin like glitter from a rave. It doesn’t need to be strong to win. It just needs to be faster, louder, and more beautiful.

And now? They’re having babies together. Hybrid MRSA. The Frankenstein of the 21st century. We didn’t just lose control of the bacteria - we gave it a Netflix series. And it’s trending.

Adam Vella

January 20, 2026 AT 20:30There is a critical oversight in the public health messaging surrounding MRSA: the distinction between colonization and infection is rarely emphasized with sufficient clarity. Many individuals erroneously equate carriage of MRSA with disease, leading to unnecessary anxiety, stigmatization, and inappropriate antibiotic use.

Furthermore, the assertion that CA-MRSA is inherently more virulent due to PVL production is not universally supported by clinical outcome data. While PVL is associated with necrotizing pneumonia and severe skin infections, its presence does not consistently correlate with worse prognosis across all populations.

Genomic surveillance is indeed imperative, but we must also invest in standardized phenotypic susceptibility testing and antimicrobial stewardship programs at the community level - not just in tertiary care centers.

Lastly, the recommendation to avoid sharing razors and towels, while prudent, is insufficient without concurrent education on biofilm formation and environmental persistence on non-porous surfaces - a topic conspicuously absent from public advisories.

Alan Lin

January 22, 2026 AT 02:35I’ve worked in ERs for 18 years. I’ve seen MRSA turn a teenager’s pimple into a life-threatening infection in 12 hours.

But here’s what no one talks about: the shame. The patient who hides their boil because they’re afraid they’ll be called "dirty" or "unhygienic." The mom who thinks she failed her kid because he got it from the wrestling team.

MRSA doesn’t care if you’re rich or poor, clean or messy. It doesn’t care if you’re an athlete or a nurse. It only cares if there’s a break in the skin and a chance to multiply.

So stop blaming. Start protecting. Wash your hands. Cover your cuts. Ask your doctor to test the bug - not just guess at it.

And if you’ve had it before? Tell them. Even if it was five years ago. That one piece of info might save your life next time.

Robin Williams

January 22, 2026 AT 09:25bro i just realized i probably had ca-mrsa last year when i got that giant boil on my butt after the camping trip. i thought it was a spider bite lol. i popped it with a pin and it felt so good but now i’m scared i spread it to my roommate. also why do we call it "methicillin-resistant" when no one even uses methicillin anymore? that’s so outdated. like calling a smartphone a "touch-tone phone" 😅

Anny Kaettano

January 23, 2026 AT 09:13As a nurse in a rural clinic, I see this every day. A kid comes in with a red, angry bump - parents say, "It’s just a pimple." But we know better. We culture it. We drain it. We don’t rush to antibiotics.

But here’s the quiet crisis: our community lacks access to labs. We send samples to the county hospital - it takes 72 hours. By then, the infection’s spread. We need point-of-care PCR testing in every small clinic - not just big cities.

And let’s talk about the stigma. Parents feel guilty. Athletes feel ashamed. People think MRSA means they’re "dirty." But it’s not about cleanliness. It’s about exposure. And we’re all exposed.

Education isn’t about fear. It’s about empowerment. Teach kids to cover wounds. Teach coaches to disinfect mats. Teach families to wash hands after the gym. Small things. Big impact.

John Tran

January 25, 2026 AT 00:09So let me get this straight - we’re living in a world where bacteria are basically doing genetic remixes like DJs at a festival? HA-MRSA brings the resistance, CA-MRSA brings the toxin, and now they’re collabing like Drake and 21 Savage? 😳

And we’re still using the same 1970s medical playbook? Bro. We need a MRSA Netflix docu-series. "The Rise of the Superbug: A Genetic Love Story."

Also, I just realized I shared a razor with my buddy last week. I’m gonna go shower in bleach. 🚿💀

vishnu priyanka

January 26, 2026 AT 14:13In India, we see this too - but with different names. We call it "hospital bug" or "gym infection." People don’t know MRSA, but they know the boil that won’t heal. No one has access to labs here. Doctors guess. They give antibiotics. Then it gets worse.

But here’s the thing - we don’t have gym towels or razors to share. We have shared water taps. Shared bathrooms. Shared beds. The transmission is quieter, but just as deadly.

Handwashing? We don’t have soap. So we use ash. It’s not perfect. But it’s what we’ve got.

MRSA isn’t a Western problem. It’s a human problem. And we’re all in the same boat.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 27, 2026 AT 21:45bro i just found out my dog has MRSA from licking my leg after i had a cut 😱 i didn’t even know pets could get it. now i’m scared to hug my puppy. also, why is it called "staphylococcus aureus"? sounds like a villain from a fantasy novel. "The Golden Staph, Lord of the Skin Plague" 🧙♂️💀

also, if you have it in your nose, does that mean you’re secretly a walking biohazard? 🤔

James Castner

January 29, 2026 AT 03:44Thank you for highlighting the systemic neglect in low-resource settings - it’s a crucial perspective often erased from Western-centric narratives. But let’s not romanticize ash as a solution. It’s a stopgap born of inequality, not ingenuity. We must demand global access to basic hygiene infrastructure as a human right, not a charity case.

And to the dog owner: yes, pets can carry MRSA. But they’re usually accidental hosts - they get it from you, not the other way around. Wash your hands after petting them, especially if you have open wounds. And yes, your puppy is not a biohazard. She’s just a loyal little germ taxi. ❤️