Partial AUC: Advanced Bioequivalence Measurements Explained

When a generic drug hits the market, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators make sure it does? Traditional measures like partial AUC and Cmax used to be enough. Today, they’re often not. For complex drug formulations-especially extended-release pills, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combination products-those old metrics can miss critical differences in how the drug is absorbed. That’s where partial AUC comes in. It’s not just another number. It’s a targeted, scientifically grounded tool that tells regulators whether a generic drug delivers the right amount of medicine at the right time.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

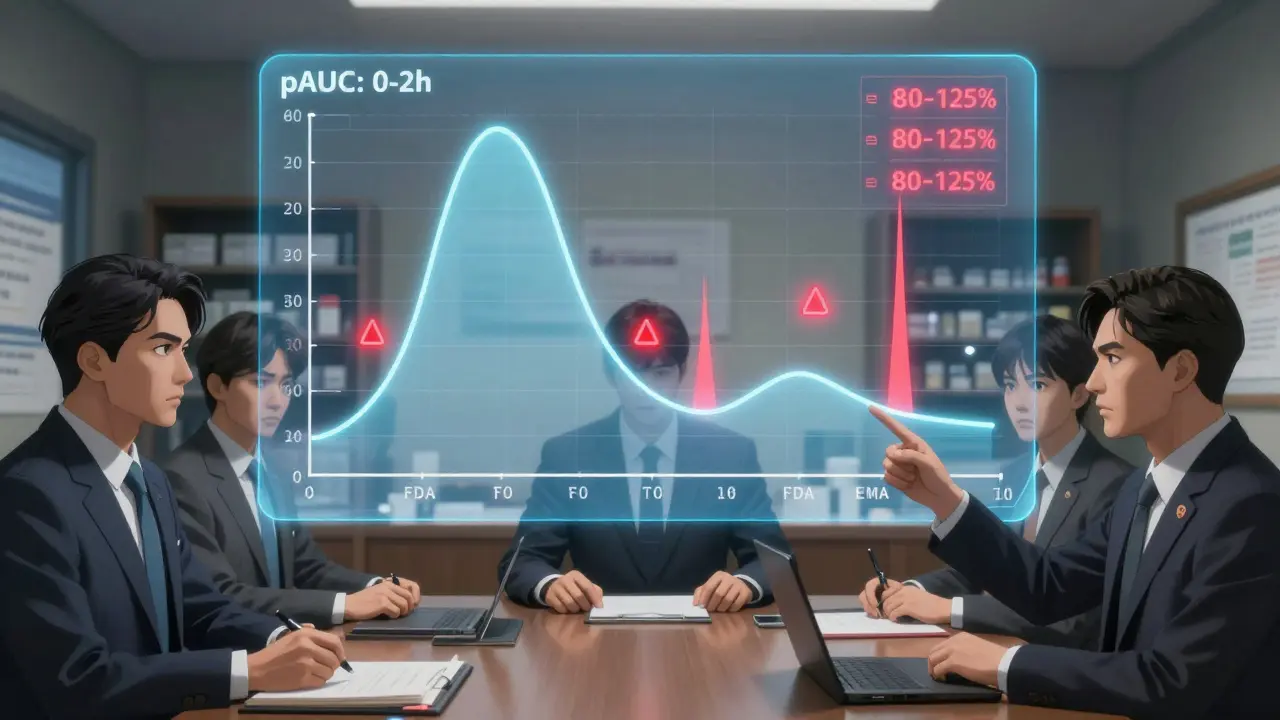

For decades, bioequivalence was judged by two main numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration of drug in the blood) and total AUC (the total drug exposure over time). These worked fine for simple, immediate-release tablets. But when a drug is designed to release slowly-like a painkiller meant to last 12 hours-those numbers can be misleading. Two products might have the same Cmax and total AUC, but one releases the drug too fast at the start, while the other releases it too slowly. The patient gets the same total dose, but the timing is off. That can mean ineffective pain control, increased side effects, or even abuse potential. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) was the first to sound the alarm in 2013. They noticed that 20% of generic drugs that passed traditional bioequivalence tests still failed to match the reference product’s absorption pattern. When they added fed and fasting studies, that failure rate jumped to 40%. That’s not a small margin of error-it’s a safety risk. The FDA followed suit. By 2017, they were explicitly saying that for certain products, Cmax and total AUC alone “might not be adequate to ensure bioequivalence.”What Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, changes the game by zooming in on a specific window of time during drug absorption. Instead of looking at the whole curve from zero to infinity, it focuses on a clinically relevant slice-say, the first two hours after dosing, or the time when drug concentrations are above 50% of Cmax. This lets regulators compare how quickly and consistently the drug enters the bloodstream, not just how much ends up there overall. The FDA’s 2017 Quantitative Modeling Workshop laid out three common ways to define the window:- Time from dosing until the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration)

- Period when drug concentration exceeds 50% of Cmax

- Interval where concentrations are above a predefined threshold

How It’s Calculated and Regulated

Calculating pAUC isn’t plug-and-play. It requires pharmacokinetic modeling software like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM. The process starts with blood samples taken at frequent intervals after dosing. Then, analysts calculate the area under the curve-only for the selected time window. The result is transformed using natural logarithms and analyzed using ANOVA, just like Cmax and AUC. The bioequivalence range still follows the standard 80-125% confidence interval. But now, that interval applies to a smaller, more meaningful part of the curve. Regulatory agencies don’t just ask for pAUC-they specify exactly when to measure it. The FDA has issued over 2,000 product-specific guidances as of 2023. About 15% of them now require pAUC. And that number is growing. In 2023, the FDA proposed adding pAUC requirements for 41 more drugs, bringing the total to 127 products where it’s mandatory. The EMA has similarly expanded its list, now recommending pAUC for 27 types of modified-release products.

Why It Matters for Real Patients

This isn’t just a regulatory technicality. It’s about safety and effectiveness. Consider extended-release stimulants used for ADHD. If the generic releases too slowly, a child might not get enough medication in the morning to focus in class. If it releases too fast, they might get jittery or lose sleep. pAUC helps ensure the timing matches the original. For cardiovascular drugs like beta-blockers, early exposure affects heart rate control. For antidepressants, it can influence how quickly symptoms improve. A senior biostatistician at Teva Pharmaceuticals shared a real-world example: their extended-release opioid generic required increasing study size from 36 to 50 subjects because pAUC introduced more variability. That added $350,000 to development costs-but it prevented a potential clinical failure. Without pAUC, the product might have passed traditional tests and gone to market, putting patients at risk.The Challenges: Cost, Complexity, and Confusion

Despite its benefits, pAUC isn’t easy to implement. One major issue: variability. Because pAUC focuses on a narrow window, small differences in individual absorption patterns can create wider swings in results. That means larger sample sizes-often 25-40% bigger than traditional studies. For small generic companies, that’s a huge financial burden. Another problem? Inconsistent guidance. Only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly explain how to pick the right time window. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 63% of developers needed extra statistical help for pAUC, compared to just 22% for standard metrics. And in 2022, 17 ANDA submissions were rejected outright because the pAUC time interval was chosen incorrectly. There’s also confusion across borders. The EMA and FDA don’t always agree on cutoff times. The IQ Consortium estimates this lack of global alignment adds 12-18 months to global drug development timelines. For patients waiting for affordable generics, that delay matters.

Who’s Using It-and Who’s Falling Behind

Adoption is strongest in therapeutic areas where timing is everything. Central nervous system drugs lead the way, with 68% of new submissions using pAUC. Pain management follows at 62%, and cardiovascular drugs at 45%. Big pharma and large generic manufacturers (those with over 500 employees) dominate usage, accounting for 92% of implementations. Smaller firms are catching up by outsourcing to specialized CROs like Algorithme Pharma, which now holds 18% of the complex generic bioequivalence market. Job postings tell the same story. As of 2023, 87% of bioequivalence specialist roles list pAUC expertise as a requirement. Biostatisticians now need 3-6 months of extra training to handle these analyses properly. The skill gap is real-and growing.What’s Next for Partial AUC?

The future of pAUC is clear: more products, more standardization, more automation. The FDA launched a pilot program in January 2023 using machine learning to recommend optimal cutoff times based on historical reference product data. The goal? Reduce subjectivity and improve consistency across submissions. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC-up from 35% in 2022. That’s not just a trend. It’s a new standard. The scientific consensus is firm: for complex formulations, traditional metrics are no longer enough. pAUC fills the gap where it matters most-between the numbers and the patient’s real-world experience.Final Thoughts

Partial AUC isn’t a fancy statistical trick. It’s a necessary evolution in how we ensure drug safety. It’s not perfect. It’s expensive. It’s complicated. But when done right, it stops unsafe generics from reaching patients. For anyone involved in generic drug development, regulatory affairs, or pharmacokinetics-understanding pAUC isn’t optional anymore. It’s the new baseline.What is partial AUC in bioequivalence studies?

Partial AUC (pAUC) measures drug exposure during a specific, clinically relevant time window-like the first two hours after dosing-instead of the entire concentration-time curve. It helps regulators compare how quickly and consistently a generic drug is absorbed compared to the brand-name version, especially for extended-release or complex formulations where total AUC and Cmax may not reveal critical differences.

Why is partial AUC used instead of total AUC?

Total AUC gives the overall drug exposure, but it can mask differences in absorption speed. For example, two products might have the same total AUC, but one releases the drug too fast at the start and the other too slowly. pAUC focuses on the absorption phase, making it more sensitive to these timing differences-especially important for abuse-deterrent, extended-release, or combination products.

How is the time window for partial AUC determined?

The time window is usually based on the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration), a percentage of Cmax (like 50%), or a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic endpoint. The FDA recommends linking the cutoff to a measurable patient outcome-like pain relief or seizure control-rather than using arbitrary time points. However, only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances currently provide clear instructions on this.

Is partial AUC required by the FDA and EMA?

Yes. Both the FDA and EMA now require pAUC for specific drug products, especially modified-release formulations. As of 2023, the FDA mandates pAUC for 127 products, and the EMA recommends it for 27 categories. This number is growing, with new product-specific guidances adding more requirements every year.

What are the main challenges of using partial AUC?

The main challenges include higher variability, which often requires larger study sizes (25-40% bigger), increased costs, lack of standardized time-interval rules across guidances, and a steep learning curve for biostatisticians. Only 42% of FDA guidances clearly define how to choose the window, leading to inconsistent submissions and regulatory rejections.

Which types of drugs most commonly require partial AUC?

Drugs with complex release profiles are most likely to require pAUC: extended-release opioids, abuse-deterrent formulations, CNS drugs like stimulants for ADHD, cardiovascular agents like beta-blockers, and combination products (e.g., immediate- and extended-release in one tablet). These are areas where timing of drug exposure directly impacts safety and effectiveness.

How does partial AUC affect generic drug development costs?

Implementing pAUC typically increases study costs by $200,000-$500,000 per product due to larger sample sizes and specialized statistical analysis. One company reported a $350,000 increase when switching from 36 to 50 subjects. Smaller companies often outsource to specialized CROs, while larger firms hire staff with advanced pharmacokinetic modeling skills.

Is partial AUC used outside the U.S. and Europe?

Yes, but inconsistently. While the FDA and EMA have clear guidelines, other regulatory agencies (like Health Canada, PMDA in Japan, and TGA in Australia) are still catching up. This lack of global alignment adds 12-18 months to international generic drug development timelines, as companies must design separate studies for different regions.