Pleural Effusion: Causes, Thoracentesis, and How to Prevent Recurrence

What Is Pleural Effusion?

When fluid builds up between the layers of tissue surrounding your lungs - called the pleura - it’s called a pleural effusion. This isn’t normal. Your lungs need space to expand fully when you breathe. Too much fluid squeezes that space, making it hard to catch your breath. You might also feel a sharp pain when you inhale, or have a dry cough. It’s not always obvious at first, but as the fluid grows, the symptoms get harder to ignore.

Every year in the U.S., about 1.5 million people develop this condition. The biggest cause? Congestive heart failure. It accounts for half of all cases. The other half usually comes from infections like pneumonia, cancer, or blood clots in the lungs. The type of fluid tells doctors what’s going on inside your body. There are two main kinds: transudative and exudative.

Transudative fluid leaks because of pressure changes - like when your heart can’t pump well enough, or your liver is failing. Exudative fluid is thicker, often bloody or cloudy, and happens when something is inflamed or cancerous. That’s why figuring out which kind you have isn’t just about comfort - it’s about survival.

How Doctors Diagnose It

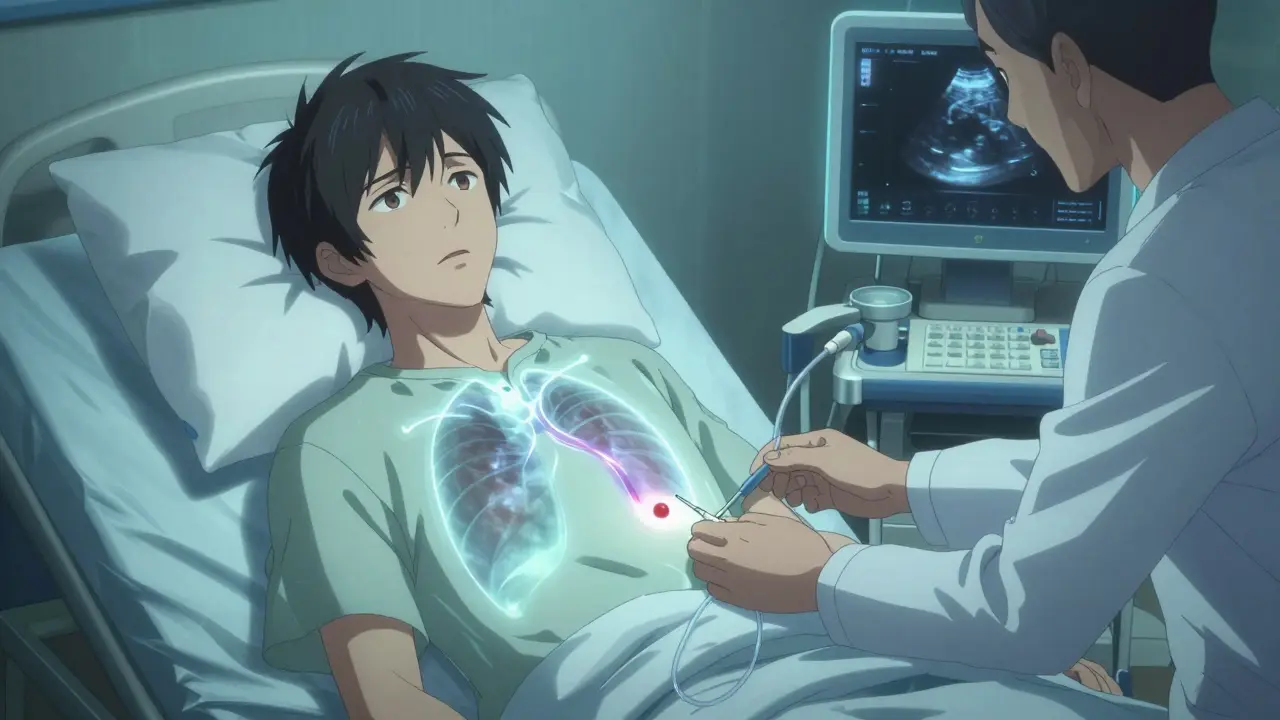

If you’re short of breath and your doctor suspects fluid around your lungs, they’ll start with an X-ray or ultrasound. But the real answer comes from taking a sample. That’s where thoracentesis comes in.

Ultrasound guidance is now standard. It’s not optional. Without it, you’re at risk for a collapsed lung. With it, complications drop by nearly 80%. The procedure is quick. You sit up, lean forward, and a thin needle is inserted between your ribs, usually around the 5th to 7th space on your side. A small amount of fluid - 50 to 100 milliliters - is pulled out for testing. If you’re struggling to breathe, they might take more - up to 1,500 milliliters in one go.

The fluid gets analyzed for five key things: protein, LDH (a liver enzyme), cell count, pH, and glucose. These numbers tell the story. For example:

- If the fluid protein is more than half of your blood protein level, or if LDH is over two-thirds of your blood LDH - that’s a sign of exudative effusion. This is called Light’s criteria, and it’s been the gold standard since 1972.

- A pH below 7.2 means the fluid is acidic, often from a complicated pneumonia. That’s a red flag for infection spreading.

- Glucose below 60 mg/dL? Could mean rheumatoid arthritis or an abscess.

- LDH over 1,000 IU/L? Often points to cancer.

- Cell count showing lots of white blood cells? Likely infection. Cancer cells? That’s a different story.

Doctors also check for amylase (high in pancreatitis) and hematocrit (if the fluid has blood, it could mean a clot or trauma). About 60% of malignant effusions are caught through cytology - looking for cancer cells under a microscope. But even then, 25% of cases are missed on the first try. That’s why follow-up tests matter.

What Is Thoracentesis, and Is It Safe?

Thoracentesis sounds scary, but it’s routine. Still, it’s not risk-free. About 1 in 10 people have a problem. The most common? A collapsed lung. That happens in 6% to 30% of cases - but only if ultrasound isn’t used. With ultrasound, that risk drops to under 5%.

Another rare but serious risk is re-expansion pulmonary edema. It happens when the lung fills back up too fast after fluid is removed. Your lung tissue gets swollen, and you can’t breathe. It’s rare - under 1% - but more likely if you drain more than 1,500 mL at once. That’s why doctors now use something called pleural manometry. It measures pressure as fluid drains. If pressure stays below 15 cm H₂O, the risk of this complication drops to just 5%.

Hemorrhage is uncommon - only 1% to 2% of cases - but can happen if a blood vessel gets nicked. That’s why the needle goes in carefully, between the ribs, not through them. Most people feel pressure, maybe a little pinch, but not sharp pain. Local anesthesia makes it tolerable.

After the procedure, you’ll get a chest X-ray to make sure your lung is still inflated. You might feel better right away - especially if you were gasping for air. But the real work starts with the lab results. That’s what guides everything next.

How to Stop It From Coming Back

Removing fluid helps you breathe - but if you don’t fix the root cause, it will come back. That’s the key. As one expert put it: “Treating the effusion without treating the cause is like bailing water from a sinking boat without patching the hole.”

For heart failure patients, the answer is medical management. Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers - these drugs reduce fluid buildup at the source. When doctors use NT-pro-BNP blood levels to guide treatment, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% in three months. No procedure needed.

For pneumonia-related effusions, antibiotics are the first step. But if the fluid is thick, infected, or has a pH under 7.2, you need drainage. Left untreated, 30% to 40% of these turn into empyema - a pocket of pus that requires surgery. Drainage before stage 2 of infection prevents that.

But the biggest challenge is cancer. Malignant pleural effusions recur in half of patients within 30 days after simple drainage. That’s why doctors now offer two long-term solutions: pleurodesis or indwelling pleural catheters.

Pleurodesis means sealing the space shut. Talc is the most common agent - it causes inflammation that glues the lung to the chest wall. It works in 70% to 90% of cases. But it’s painful. Up to 80% of patients need strong pain meds after. Hospital stays are longer - about 7 days on average.

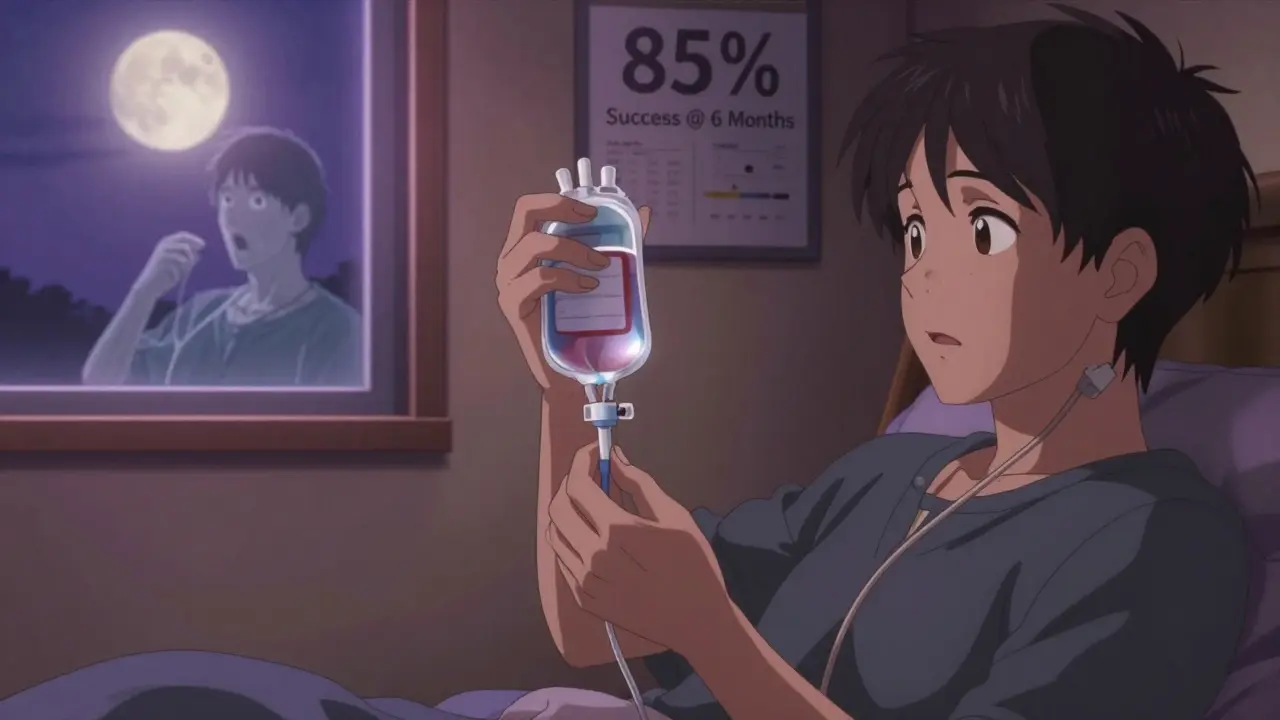

Indwelling pleural catheters are changing the game. These are small tubes left in place for weeks. You or a caregiver can drain fluid at home, as needed. Success rates? 85% to 90% at six months. Hospital stays drop to just 2 days. And patients report better quality of life. The European Respiratory Society now recommends them as first-line for recurrent malignant effusions.

What Doesn’t Work - And Why

Not every fluid collection needs to be drained. A 2019 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 30% of thoracenteses were done on small, asymptomatic effusions - and didn’t help at all. You don’t need to drain a 5mm fluid layer if you’re not short of breath. That’s unnecessary risk.

Also, chemical pleurodesis isn’t recommended for non-cancer cases. It doesn’t work well for heart failure or liver disease. The inflammation it causes can hurt more than help. Guidelines from the American Thoracic Society say: don’t do it. Stick to treating the underlying disease.

And while ultrasound is now standard, not every clinic has it. In rural areas or smaller hospitals, some doctors still rely on old-school techniques. That’s dangerous. Complication rates jump from 4% to nearly 20% without imaging. If your doctor doesn’t use ultrasound, ask why.

What’s New in 2026

The biggest shift in the last five years is personalization. We’re no longer treating all malignant effusions the same. A lung cancer patient with good performance status might do better with a catheter. Someone with advanced cancer and poor mobility might prefer talc pleurodesis for a one-time fix. Survival rates have improved - from 10% to 25% over the last decade - because we’re matching treatment to the cancer type and the person’s overall health.

Emerging tools like pleural manometry are making drainage safer. Biomarker panels are being tested to predict which effusions will become infected before they turn serious. And new sclerosing agents are being studied to reduce the pain of pleurodesis.

The message is clear: treat the cause, not just the symptom. Use ultrasound. Don’t drain unless needed. And for cancer-related fluid - consider the catheter. It’s not just a procedure. It’s a lifestyle change that gives you control back.

Kelly Weinhold

January 30, 2026 AT 13:32Man, I had a pleural effusion last year after pneumonia and honestly? Thoracentesis was way less scary than I thought. Felt like a weird pressure, not pain. And the relief after they drained it? Like someone unclamped my chest. I didn’t even know I was breathing so shallow until I wasn’t.

They kept me overnight just to watch me, but honestly? Worth it. I’m still on antibiotics, but my doctor said if it comes back, we’re talking catheter, not talc. No way I’m going through that pain again.

Natasha Plebani

January 30, 2026 AT 14:31The real epistemological rupture in modern pleural management isn’t the procedure-it’s the ontological shift from symptom eradication to causal ontology. Light’s criteria, while statistically robust, remains a heuristic artifact of 20th-century diagnostic positivism. We’re now entering an era where proteomic signatures, not LDH ratios, will define exudative vs. transudative classification.

Consider the emerging role of microRNA panels in malignant effusions: miR-21 and miR-155 show >92% specificity in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma detection, far surpassing cytology’s 60% sensitivity. The paradigm is no longer ‘drain and diagnose’-it’s ‘predict, stratify, personalize.’

And yet, we still rely on 1972-era algorithms in rural clinics because reimbursement models haven’t evolved. This isn’t medicine. It’s diagnostic colonialism.

Jason Xin

January 31, 2026 AT 10:52Yeah, ultrasound isn’t optional. I’ve seen the X-ray before and after-without it, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with a needle between ribs. One guy I worked with got a pneumothorax because they ‘just felt it.’ Took him three weeks to recover.

And don’t get me started on people draining 2 liters just because they can. Pleural manometry isn’t fancy-it’s common sense. Pressure stays under 15 cm H₂O? You’re fine. Go past that? You’re asking for re-expansion edema. Simple math.