Post-Transplant Infections: How to Prevent, Vaccinate, and Monitor After Kidney Transplant

Why Infections Are the Biggest Threat After a Kidney Transplant

After a kidney transplant, your new organ isn’t the only thing your body has to accept. Your immune system, now turned down by powerful drugs to stop rejection, can’t fight off the germs it used to handle easily. That’s why post-transplant infections are the leading cause of hospitalization and death in the first year after surgery. You might feel fine, but bacteria, viruses, and fungi that once caused a cold or minor rash can now turn deadly.

It’s not random. Your risk depends on three things: how strong your immunosuppressants are, what germs you were exposed to before and after transplant, and how well you follow prevention steps. The biggest threats aren’t just hospital bugs-they’re everyday ones. Listeria in soft cheese. CMV from a loved one’s saliva. Aspergillus spores in garden soil. Even your pet cat can carry toxoplasma.

Three Pillars of Infection Prevention: Medicine, Vaccines, and Lifestyle

There’s no single fix. Preventing infections after transplant works like a three-legged stool: medicines, vaccines, and daily habits. Lose one, and the whole system wobbles.

Medicines: The First Line of Defense

Right after transplant, you’ll be on a cocktail of preventive drugs-antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals. These aren’t for treating illness. They’re for stopping it before it starts.

- For herpes viruses like HSV and VZV, you’ll take acyclovir or valacyclovir for 1 to 3 months. This prevents mouth sores and shingles.

- For CMV (cytomegalovirus), the most dangerous virus after transplant, your team will check your and your donor’s blood before surgery. If you’re negative and your donor is positive (D+/R-), you’re high risk. You’ll get valganciclovir for 3 to 6 months. This cuts your risk of CMV disease by over 70%.

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) used to kill half of transplant patients. Now, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) taken once daily for 6 to 12 months prevents it in nearly all cases.

- For fungal infections like candida or aspergillus, fluconazole or posaconazole may be added, especially if you had a long ICU stay or received strong steroids.

These drugs aren’t forever. Stopping them too early can trigger infection. Stopping them too late raises your risk of drug side effects and antibiotic resistance.

Vaccines: Timing Is Everything

Most vaccines you had before transplant? They’re probably useless now. Your immune system was reset. You need to rebuild protection-safely.

- Before transplant: Get all routine vaccines (flu, pneumococcal, hepatitis B, Tdap, MMR if you’re immune-deficient) at least 4 weeks before surgery. This is your last chance to build strong immunity.

- After transplant: Wait at least 6 months. Then, you can get inactivated vaccines: flu shot, Tdap, pneumococcal (Prevnar 13 and Pneumovax 23), and hepatitis B if you never had it. These are safe because they don’t contain live viruses.

- Avoid live vaccines: Never get MMR, varicella (chickenpox), or nasal flu spray after transplant. They can cause the disease they’re meant to prevent.

- Family vaccination: Your household members should be up to date on flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 shots. This creates a "cocoon" around you-less chance they’ll bring germs home.

Many patients don’t realize they need a second pneumococcal shot a year after the first. Others skip the flu shot because they think, "I got it last year." But flu strains change every season. You need it every fall.

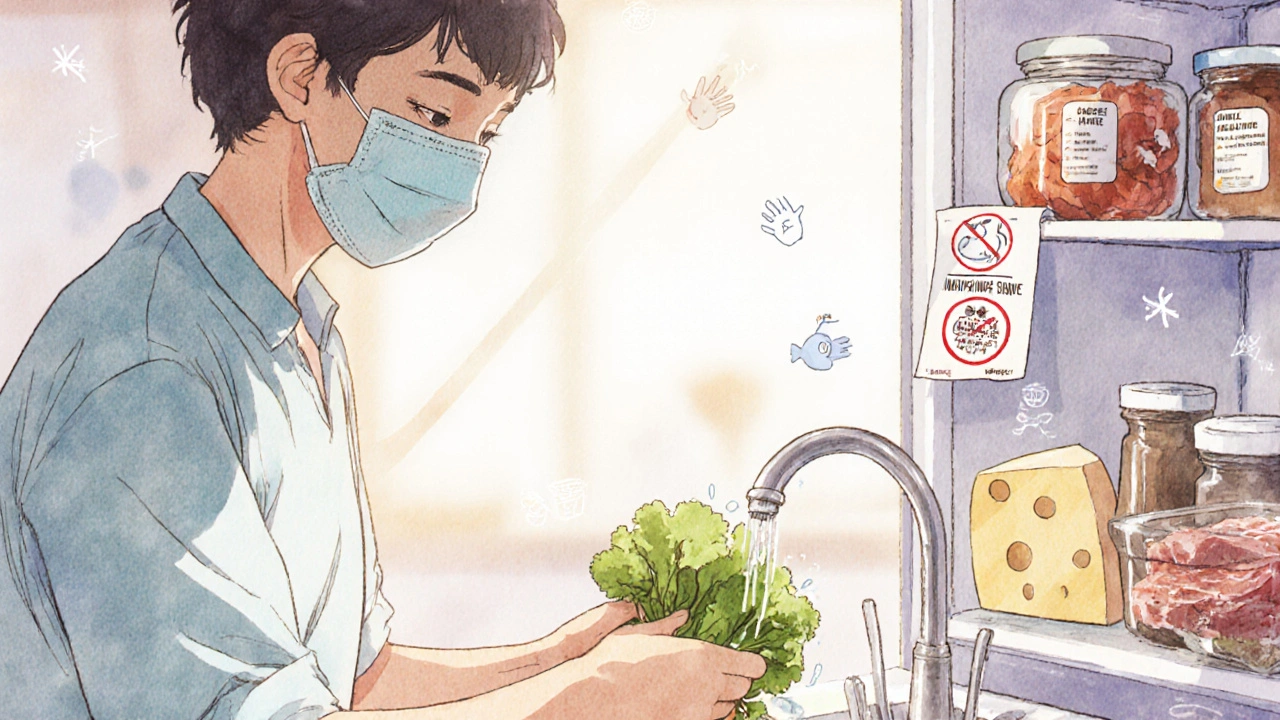

Lifestyle: What You Do Every Day Matters More Than You Think

Medicines and vaccines protect you from inside. Lifestyle protects you from outside.

- Food safety: No raw fish, undercooked meat, or unpasteurized cheese. Listeria grows in deli meats, soft cheeses like brie, and even refrigerated smoked salmon. Cook everything to safe temperatures. Wash fruits and veggies even if you peel them.

- Water: Avoid hot tubs, swimming pools with poor chlorine levels, and untreated well water. Use bottled water if your tap water is from a private source.

- Soil and plants: Wear gloves when gardening. Soil in Ohio, the Midwest, and parts of the South carries histoplasmosis. Avoid cleaning bird cages or bat droppings.

- Pets: Cats can carry toxoplasma. Don’t change litter boxes. Dogs can carry salmonella. Wash hands after petting. Avoid reptiles, birds, and exotic pets-they’re high-risk.

- Hand hygiene: Wash hands with soap and water for 20 seconds. Use alcohol gel if soap isn’t available. Do it before eating, after using the bathroom, and after touching public surfaces.

- Masking: Wear a mask in crowded places like hospitals, public transit, or during flu season. Respiratory viruses like RSV and influenza spread fast in winter and can cause pneumonia in transplant patients.

One patient I know got sick from a garden hose left on the porch. The water pooled, grew mold, and when he sprayed it on his roses, he inhaled the spores. He ended up in the ICU with aspergillosis. It’s not paranoia. It’s science.

Monitoring: Catching Infections Before They Strike

You can’t wait for symptoms. By the time you have a fever or cough, the infection may already be advanced.

Regular monitoring is non-negotiable. Here’s what it looks like:

- CMV: Blood tests every 1 to 2 weeks for the first 3 months, then monthly for up to a year. Quantitative PCR detects viral DNA before you feel sick. If levels rise, you start antivirals immediately-this is called preemptive therapy.

- Fungal infections: Blood tests for beta-D-glucan and galactomannan. These biomarkers rise days before symptoms appear, especially in HSCT patients.

- MDR organisms: If you’ve had a recent hospital stay or antibiotic use, your team may screen your stool or nasal swabs for resistant bacteria like MRSA or ESBL-producing E. coli. Weekly screening is common in high-risk units.

- General blood work: CBC, liver, and kidney tests every 1 to 2 weeks early on. A drop in white blood cells or rising creatinine can signal infection before you notice anything else.

Some clinics now use wearable devices that track temperature and heart rate trends. A small, unexplained rise over 48 hours can trigger a call from your nurse before you even feel ill.

The New Frontiers: FMT, Anti-Adhesion Therapies, and Personalized Prevention

The field is changing fast. What worked in 2015 isn’t enough today.

One major problem: multidrug-resistant bacteria. One in three bacterial infections in transplant patients now involves germs that don’t respond to standard antibiotics. These often come from your own gut-colonized during hospital stays or from antibiotics you took before transplant.

New strategies are emerging:

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): Originally for C. diff, FMT is now being tested to "reset" the gut microbiome in transplant patients colonized with MDR bacteria. Early results show it reduces colonization by over 60%.

- Anti-adhesion therapies: Instead of killing bacteria, these drugs block them from sticking to your bladder or gut lining. Think of it like putting Teflon on your cells so germs can’t grab on.

- Letermovir: A new antiviral approved for CMV in HSCT patients. It’s safer than ganciclovir and can be used beyond 100 days post-transplant-filling a dangerous gap when older drugs stop.

- CMV vaccines: Several are in phase 3 trials. If approved, they could one day replace lifelong prophylaxis. But none are available yet.

Soon, prevention won’t be one-size-fits-all. Blood tests will measure your immune function. If your T-cell count is low, you’ll get longer antivirals. If your gut microbiome is healthy, you might skip some antibiotics. Personalized prevention is coming-and it’s already being tested in Dublin, Toronto, and Boston.

What Happens After 6 Months? The Silent Risk

Many patients think, "I’m past the danger zone." But the biggest risk isn’t in the first month-it’s after prophylaxis stops.

At 6 months, most people reduce immunosuppressants. But your immune system is still weak. CMV can flare up. Fungal infections can hide in your lungs. Community viruses like RSV and parainfluenza hit hard.

Don’t drop your guard. Keep washing hands. Keep wearing masks in winter. Keep getting your flu shot. Keep avoiding risky foods. Your transplant team will keep monitoring you-every 3 months for the first year, then every 6 months after that. Don’t skip appointments. Don’t ignore a low-grade fever. It might be nothing. Or it might be your body’s only warning.

Final Thought: Prevention Is a Lifelong Habit, Not a Phase

You didn’t just get a new kidney. You got a new responsibility. Infection prevention isn’t something you do for a year. It’s something you live.

It’s not about fear. It’s about control. You can’t control your immune system. But you can control your hands, your food, your masks, your vaccines, and your follow-ups. Do those right, and your transplant lasts longer. You live better. You’re less likely to end up back in the hospital.

Ask your team for a printed checklist. Keep it on your fridge. Review it every month. You’ll thank yourself in five years.

Lisa Detanna

November 23, 2025 AT 04:58Demi-Louise Brown

November 24, 2025 AT 17:21Pramod Kumar

November 25, 2025 AT 02:40Katy Bell

November 25, 2025 AT 03:20Jennifer Shannon

November 26, 2025 AT 17:37Suzan Wanjiru

November 27, 2025 AT 16:46Manjistha Roy

November 29, 2025 AT 07:41Jennifer Skolney

December 1, 2025 AT 06:38JD Mette

December 1, 2025 AT 18:35Olanrewaju Jeph

December 3, 2025 AT 00:58Dalton Adams

December 3, 2025 AT 04:56