Senior Patient Education: Effective Materials for Older Adults

Why Senior Patient Education Needs to Be Different

Most health materials are written for people in their 30s and 40s. That’s a problem for older adults. By age 65, nearly 8 out of 10 people struggle with medical forms, medication labels, or even understanding simple instructions like "take with food." It’s not because they’re not smart-it’s because the materials weren’t made for them.

The National Institute on Aging found that 71% of adults over 60 have trouble reading standard health brochures. That’s not a small number. It’s the majority. And when people don’t understand their treatment, they skip doses, show up in the ER, or end up back in the hospital. The good news? Simple changes in how we deliver information make a huge difference.

What Makes Good Materials for Seniors?

Effective senior patient education isn’t just about using bigger words. It’s about designing for how aging changes the way people see, think, and remember.

First, font size matters. Text must be at least 14-point, and never use small, thin fonts like Arial Narrow. Stick to clean, bold typefaces like Verdana or Tahoma. Letters like "l," "1," "O," and "0" can look identical to someone with poor vision. Always spell them out: "L as in Lily," "O as in Orange."

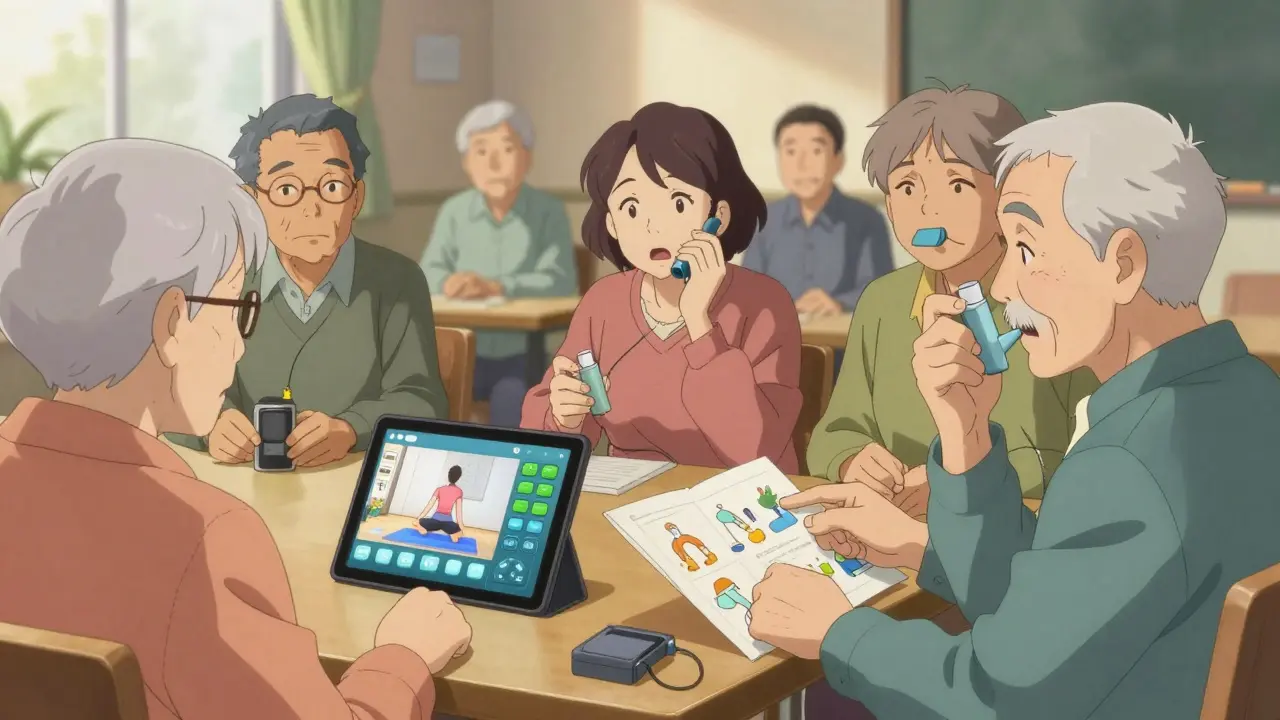

Second, keep it short. One-page handouts work better than five-page booklets. If you need to explain how to use an inhaler, use pictures. The American Geriatrics Society found that illustrated step-by-step guides improved medication adherence by 37% compared to text-only instructions.

Third, use plain language. Don’t say "hypertension." Say "high blood pressure." Don’t say "polypharmacy." Say "taking five or more pills a day." The goal is a 3rd to 5th grade reading level. That’s not dumbing down-it’s making sure the information reaches the person who needs it.

How to Use Multiple Ways to Teach

People don’t learn the same way. Some prefer to hear it. Others need to see it. Some learn by doing.

Good senior education uses all three. A handout about diabetes might include:

- A simple drawing of a plate showing what to eat

- A short video showing how to check blood sugar

- A voice-recorded version you can listen to on a phone

The CDC recommends testing materials with real older adults before finalizing them. That means asking 15 or more seniors to read the material and explain it back in their own words. If they can’t explain it simply, rewrite it.

HealthinAging.org, run by the American Geriatrics Society, has over 1,300 free materials like this. Their guide on "Understanding Your Medications" uses photos of pill bottles, color-coded boxes, and a simple checklist. It’s been downloaded over 2 million times since 2020.

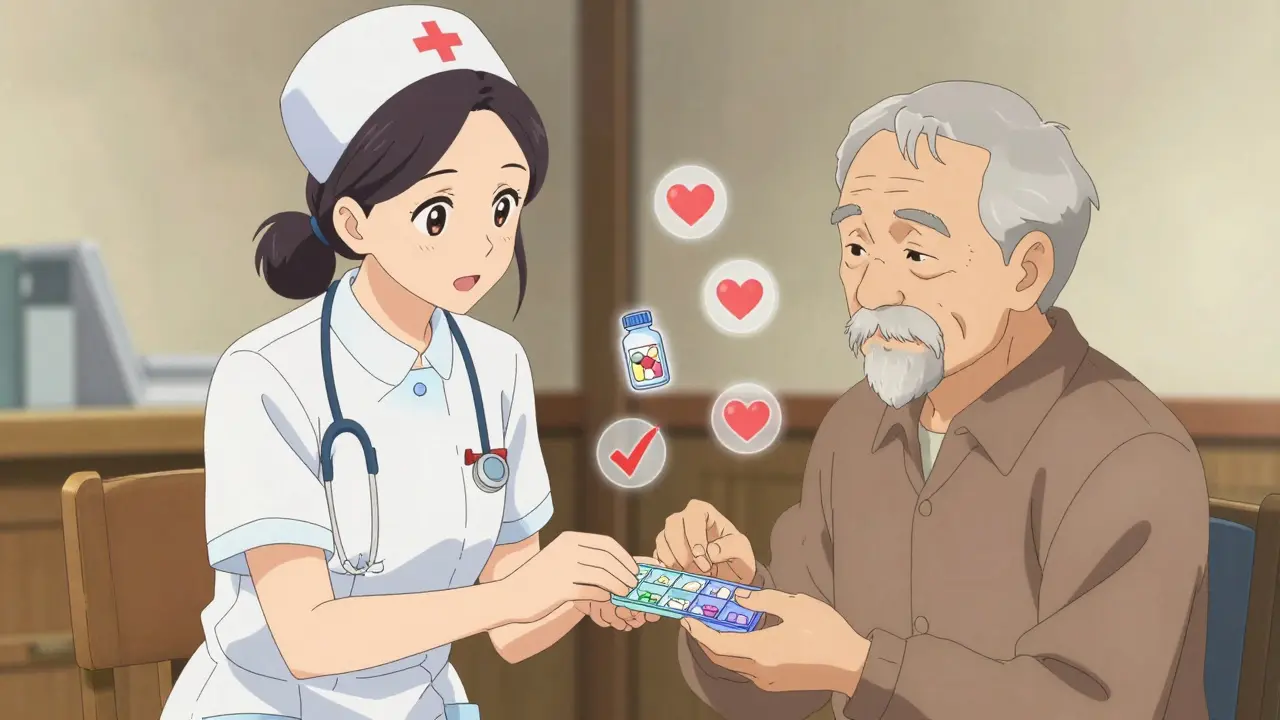

The Teach-Back Method: The Secret Weapon

Doctors and nurses often ask, "Do you understand?" But older adults often say yes-even when they don’t. Why? They don’t want to seem confused or be seen as a burden.

The solution? Teach-back. Instead of asking if they understand, ask them to show you. "Can you tell me how you’ll take this pill each day?" or "Show me how you’d use this inhaler?"

A 2022 study in Patient Education and Counseling found that when providers used teach-back, patients understood their treatment 31% better-even though the visit only took 2.7 extra minutes. That’s a tiny time investment for a huge result.

It’s not about testing them. It’s about making sure the message landed. And it works for everything: post-surgery care, heart failure diets, insulin injections, even how to call for help if they fall.

Why So Many Programs Still Fail

Even though the evidence is clear, most clinics still don’t use these methods. A 2023 survey by the American Medical Association found that 78% of providers said they didn’t have enough time. Another 65% said they didn’t have the budget to create better materials.

And here’s the hard truth: many healthcare systems still treat health literacy as an afterthought. They print a brochure, hand it out, and move on. But research shows that without proper design and testing, those materials are useless-or worse, dangerous.

Only 28% of U.S. healthcare systems have fully adopted what’s called "universal precautions for health literacy." That means assuming everyone might struggle and designing everything to be clear from the start.

But it’s changing. Medicare hospitals that use full senior education programs see 14.3% fewer readmissions. That’s not just better care-it’s $1,842 saved per patient. When you multiply that across thousands of seniors, it adds up to millions saved each year.

Technology Can Help-But It’s Not the Answer Alone

More seniors are using telehealth now than ever. In 2023, 68% of older adults had a virtual doctor visit, up from just 17% in 2019. That’s progress.

But tech alone doesn’t fix poor communication. A video that’s too fast, a website with tiny text, or a voice assistant that doesn’t understand "my pill bottle is blue" won’t help.

The National Institute on Aging updated its Go4Life exercise program in January 2024 to include voice-guided instructions and large-button video controls. That’s the right direction. But tech must be designed with seniors-not just added on.

Some new tools use AI to adjust content based on how someone responds. If a person takes longer to answer a question, the system slows down. If they skip a picture, it adds more visuals. This kind of personalization is still new, but it’s promising.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re a caregiver, family member, or older adult yourself, here’s what works:

- Ask for materials in large print or audio format. You have the right to ask.

- Use the teach-back method after every appointment. Say: "Can you explain this back to me so I’m sure I got it?"

- Visit HealthinAging.org or MedlinePlus.gov. Both offer free, easy-to-read materials on over 200 topics-from managing arthritis to understanding advance directives.

- Keep a simple medication list: name, dose, time, purpose. Use a pill organizer with clear labels.

- If something doesn’t make sense, say so. No one should feel embarrassed for asking.

The Bigger Picture

By 2040, one in five Americans will be over 65. That’s 80 million people. If we keep using the same old handouts, we’ll keep seeing preventable hospital visits, medication errors, and declining health.

But if we design materials with real older adults in mind-big fonts, simple words, pictures, voice, and teach-back-we can change that. We can help people stay healthy longer, live independently, and feel more in control of their care.

This isn’t just about printing better brochures. It’s about treating older adults with respect. Giving them the tools they need-not the ones we assume they should want.

What reading level should senior patient education materials be written at?

Senior patient education materials should be written at a 3rd to 5th grade reading level. This is based on CDC and National Institute on Aging guidelines, which found that this level improves understanding by 42% compared to standard medical materials. Even though the average American reads at a 7th to 8th grade level, many older adults-especially those with limited health literacy-need simpler language to understand their care.

Is it okay to use pictures instead of text in senior health materials?

Yes, pictures are not just okay-they’re essential. The American Geriatrics Society found that illustrated step-by-step instructions improved medication adherence by 37% among older adults with low health literacy. Clear images of pill bottles, handwashing steps, or how to use an inhaler can communicate more than paragraphs of text. Always pair pictures with short, bold captions using large fonts.

Why do older adults often say they understand when they don’t?

Many older adults don’t want to appear confused, embarrassed, or like a burden. They may fear being judged or think they should already know. A 2022 National Council on Aging survey found that 51% of seniors never asked for clarification-even when they didn’t understand. That’s why the teach-back method is so important: it invites them to explain, rather than just answer yes or no.

Where can I find free, easy-to-read health materials for seniors?

Two trusted sources are HealthinAging.org, run by the American Geriatrics Society, and MedlinePlus.gov, from the National Institutes of Health. Both offer hundreds of free, plain-language resources on topics like diabetes, heart disease, dementia, and medication safety. All materials are reviewed by experts and tested with older adults. They’re available in print, audio, and online formats.

Can technology like tablets or voice assistants help seniors understand health info?

Yes-but only if they’re designed for seniors. A tablet with tiny text or a voice assistant that doesn’t understand "my blue pill" won’t help. Tools like the updated Go4Life program from the National Institute on Aging use large buttons, slow speech, and voice-guided instructions. The key is simplicity: one task at a time, no clutter, and the option to hear it spoken aloud. Technology should support, not replace, clear communication.

How long does it take to create good senior patient education materials?

Creating one effective patient education resource takes 8 to 12 weeks. It involves writing, designing, testing with at least 15 older adults, rewriting based on feedback, and reviewing with medical experts. HealthPartners Institute, which has over 1,300 materials in their database, follows this process for every handout and guide. Rushing it leads to confusion-and that can be dangerous.

Jerry Rodrigues

January 21, 2026 AT 15:31Gerard Jordan

January 23, 2026 AT 09:06Roisin Kelly

January 25, 2026 AT 05:05lokesh prasanth

January 25, 2026 AT 12:15Coral Bosley

January 26, 2026 AT 12:37Uju Megafu

January 28, 2026 AT 05:38Melanie Pearson

January 29, 2026 AT 03:09MAHENDRA MEGHWAL

January 29, 2026 AT 13:04michelle Brownsea

January 29, 2026 AT 18:05