Special Populations in Bioequivalence: Age and Sex Considerations

When a generic drug hits the market, it’s supposed to work just like the brand-name version. But what if the people taking it aren’t the same as the ones who tested it? For decades, bioequivalence (BE) studies - the clinical trials that prove generics are safe and effective - were done almost exclusively on young, healthy men. That’s not just outdated. It’s risky. Today, regulators are forcing a change. And the reasons have everything to do with age and sex.

Why bioequivalence studies used to ignore women and older adults

Bioequivalence studies measure how quickly and how much of a drug enters your bloodstream. The goal? Show that two versions - say, a generic and the original - behave the same way. For years, the standard was simple: recruit 12 to 24 healthy men, ages 18 to 30, with no chronic conditions. Why? Because they were seen as the most predictable group. Their bodies processed drugs consistently. Their hormone levels didn’t fluctuate. They weren’t pregnant. Easy to control. Easy to measure. But here’s the problem: most drugs aren’t taken only by young men. Take levothyroxine, a common thyroid medication. Over 60% of users are women. Yet BE studies for it often included fewer than 25% women. That’s not just a gap. It’s a blind spot. The same goes for older adults. Many medications - for high blood pressure, arthritis, or cholesterol - are taken primarily by people over 60. But BE studies rarely included them. Why? Because older bodies absorb, metabolize, and clear drugs differently. Kidney and liver function slow down. Body fat increases. Muscle mass drops. All of this changes how a drug behaves. But if you only test it on a 25-year-old man, how do you know it’s safe for a 72-year-old woman?Regulators are finally catching up

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed the game in 2013, then again in May 2023. Their new draft guidance says this: if a drug is meant for both men and women, your BE study must include roughly equal numbers of each. No exceptions unless you can prove why. And if the drug is mostly used by older people, you need to include adults over 60 - or explain why you didn’t. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been slower. Their 2010 guideline says subjects “could belong to either sex,” which sounds open-minded - until you realize it doesn’t require balance. Still, they’re reviewing the rule in 2024. Brazil’s ANVISA is already ahead: they demand equal male-female splits and limit participants to ages 18 to 50. Canada allows 18 to 55. But only the FDA now demands representation that matches real-world use. This isn’t just about fairness. It’s about safety. In one 2017 study, a generic drug looked bioinequivalent in men - meaning it didn’t absorb the same way - but was perfectly fine in women. The difference? A small sample size of just 14 people. In a larger follow-up with 36 participants, the difference vanished. That’s the danger of small, unbalanced studies: they create false alarms or miss real problems.

What the rules actually require today

Let’s break down what sponsors must do now - especially under the FDA’s 2023 draft:- Age: Participants must be 18 or older. If the drug targets older adults (like those with osteoporosis or heart failure), you must include people aged 60+. If you exclude them, you need a solid scientific reason - not just convenience.

- Sex: If the drug is used by both men and women, aim for a 50:50 split. If it’s only for one sex - say, prostate cancer drugs for men or birth control for women - only include that sex.

- Health status: The FDA allows people with stable chronic conditions (like controlled diabetes or high blood pressure) if the drug doesn’t interfere with the study. EMA and ANVISA still require healthy volunteers only.

- Exclusions: No pregnant or breastfeeding women. All women of childbearing potential must use contraception or abstain.

- Sample size: EMA says minimum 12 evaluable subjects. But real-world studies now enroll 24 to 36 to catch subtle differences between sexes or age groups.

The hidden cost of imbalance

It’s not just science - it’s money. Recruiting women for BE studies takes longer and costs more. Sites report 40% longer timelines when targeting gender balance. Why? Women are less likely to volunteer for clinical trials. They juggle caregiving, work, or fear side effects. Some studies have tried incentives, flexible hours, or childcare - but adoption is still patchy. And here’s the kicker: even when women are included, their data isn’t always analyzed separately. A 2021 FDA review of 1,200 generic drug applications found that only 38% had female participation between 40% and 60%. The median? Just 32%. That means most BE studies still don’t reflect the people who will actually take the drug. One example: the blood thinner apixaban. Over half of users are women. Yet BE studies for its generics often had fewer than 30% female participants. What happens if women metabolize the drug differently? A tiny difference in absorption could mean bleeding risk - a life-threatening side effect.

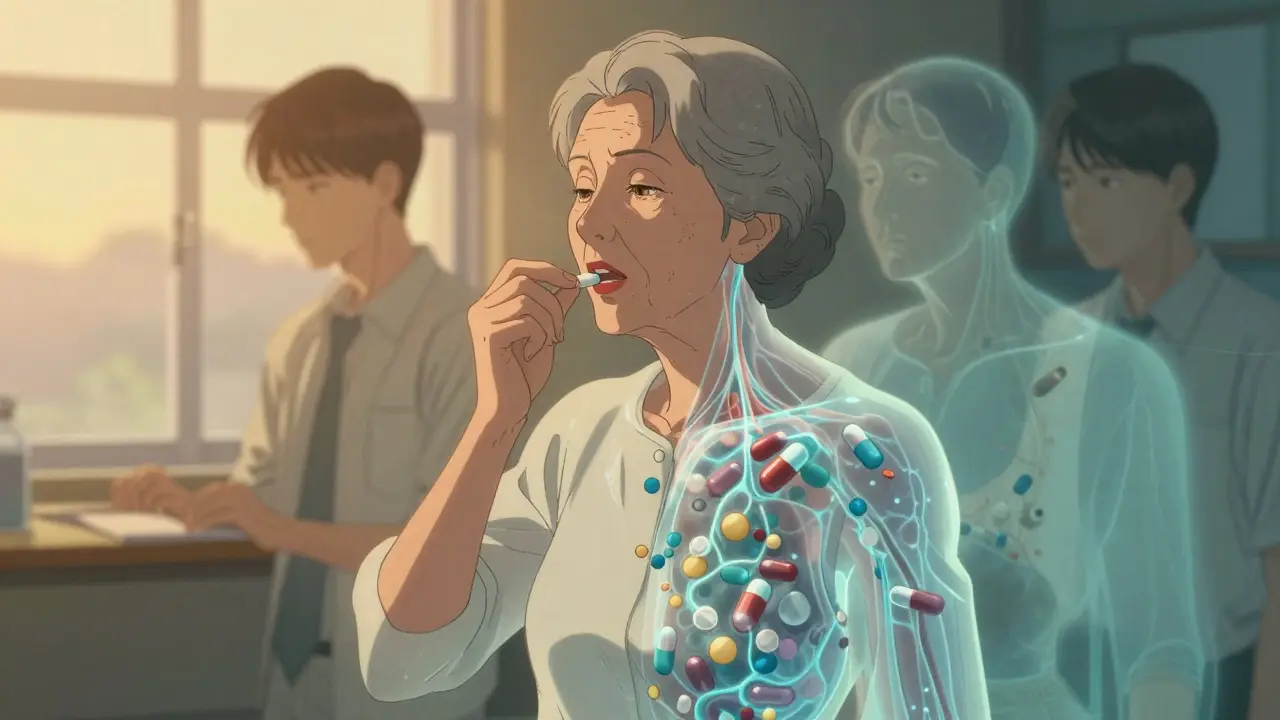

What’s next? Science is catching up

New research is showing that sex differences aren’t rare - they’re common. A 2023 study from the University of Toronto found that 37% of commonly tested drugs are cleared 15% to 22% faster in men than in women. That’s not noise. That’s biology. Women have higher body fat percentages. Different liver enzyme activity. Slower gastric emptying. All of this affects how drugs work. The National Academies of Sciences recommended in 2021 that regulators create sex-specific bioequivalence criteria for narrow therapeutic index drugs - like warfarin, digoxin, or lithium - where even small changes can be dangerous. That’s coming. The FDA’s 2023-2027 plan explicitly names “enhancing representation of diverse populations” as a top priority. That means sponsors who ignore age and sex won’t just get flagged - they’ll get rejected.What this means for patients

You don’t need to know the details of pharmacokinetics. But you should know this: if you’re a woman over 50 taking a generic drug, the study that proved it was “equivalent” might not have included anyone like you. That’s changing. Slowly. But it’s changing. The push for inclusive bioequivalence isn’t about political correctness. It’s about science. It’s about safety. And it’s about making sure that when you swallow a pill - no matter your age or sex - it works the way it should.Key takeaway: Bioequivalence isn’t just about chemistry. It’s about people. And people aren’t all young, healthy men.