TNF Inhibitors: How Biologics Work for Autoimmune Conditions

TNF inhibitors are not magic pills. They don’t cure autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or Crohn’s disease. But for millions of people, they’ve turned life-threatening inflammation into something manageable. These drugs didn’t just tweak symptoms-they rewrote the rules of treatment. Before TNF inhibitors, many patients faced slow, steady joint destruction, constant pain, and no real hope of getting back to normal life. Now, people who couldn’t walk are hiking. Those who spent nights in ERs with flare-ups are back at work. This isn’t hype. It’s science-and it’s real.

What Exactly Is TNF Alpha?

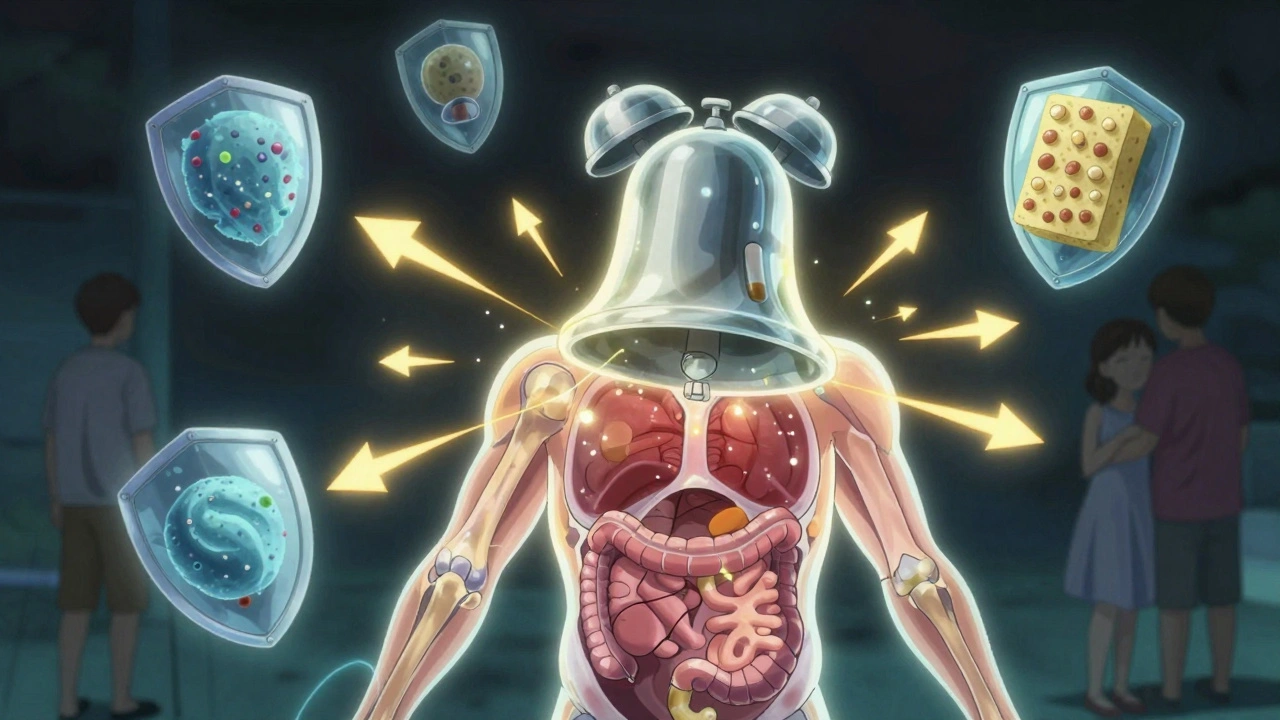

Think of TNF alpha as the alarm bell in your body’s immune system. When something goes wrong-like an infection or tissue damage-it rings loudly to call in reinforcements: white blood cells, more inflammation, more activity. That’s normal. But in autoimmune diseases, the alarm never turns off. It rings even when there’s no real threat. Your own body starts attacking your joints, skin, or gut. TNF alpha sits right at the top of this faulty alarm chain. It’s the signal that triggers other inflammatory chemicals like IL-1 and IL-6. It tells blood vessels to open up so immune cells can flood into tissues. It makes cells stick together so they can team up and cause damage. Without TNF alpha, this whole chain collapses.

It’s not just bad. TNF alpha has useful jobs too. It helps fight off bacteria like tuberculosis and helps regulate immune cell growth. That’s why turning it off completely can be risky. But in autoimmune conditions, it’s like having a fire alarm that goes off every time someone walks by. The solution isn’t to silence all alarms-it’s to silence just the broken one.

The Five TNF Inhibitors You Need to Know

The FDA has approved five TNF inhibitors for use in the U.S. Each one works differently, and that matters a lot.

- Etanercept (Enbrel): This one isn’t an antibody. It’s a fusion protein-a lab-made piece that looks like part of the TNF receptor. It acts like a sponge, soaking up free-floating TNF alpha before it can latch onto your cells. You inject it once or twice a week.

- Infliximab (Remicade): A full monoclonal antibody. It binds to both soluble and cell-bound TNF. It’s given through an IV, usually every 4 to 8 weeks. Because it’s made from mouse and human proteins, some people develop antibodies against it over time.

- Adalimumab (Humira): Also a monoclonal antibody, but fully human. That means fewer immune reactions. You inject it under the skin every other week. It’s one of the most prescribed biologics in the world.

- Golimumab (Simponi): Another fully human antibody. Given once a month. It’s often used for people who need less frequent dosing.

- Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia): The odd one out. It’s a fragment of an antibody, attached to polyethylene glycol (PEG). It only binds to soluble TNF, not the kind stuck to cell surfaces. It’s the only TNF inhibitor that doesn’t trigger cell death in immune cells, which might explain why it’s sometimes used in pregnancy.

These differences aren’t just technical. They affect how often you get treated, how you get it (shot vs. IV), and even how likely your body is to reject it. Some people respond better to one than another-not because of luck, but because of how their immune system reacts to the drug’s shape.

How Do They Actually Stop Inflammation?

TNF inhibitors don’t just block a signal. They reset a whole system.

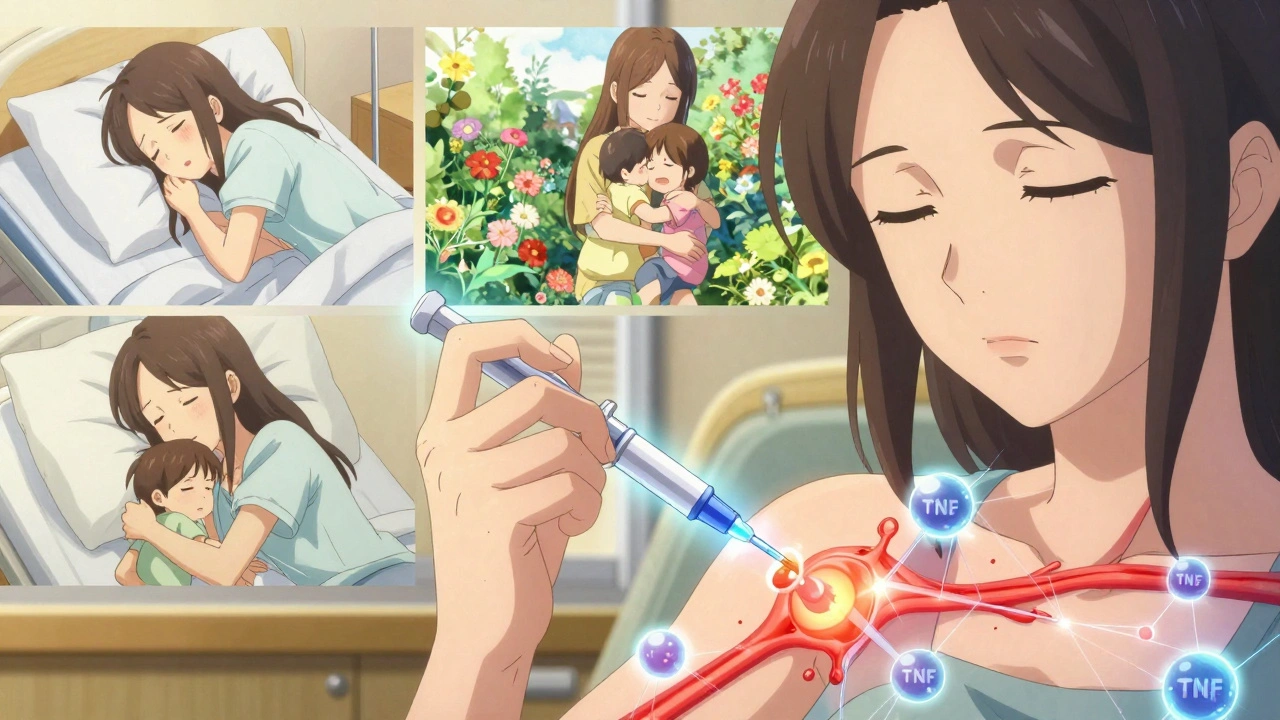

When TNF alpha binds to its receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2), it turns on pathways that make cells release more inflammation, attract immune cells, and even trigger cell death. TNF inhibitors block this. But here’s the twist: they do it in different ways.

Monoclonal antibodies like adalimumab and infliximab don’t just block TNF. They can also flag immune cells for destruction. Think of it like painting a target on a cell. Your own immune system then comes in and kills it. That’s called antibody-dependent cytotoxicity. Etanercept doesn’t do that. It just mops up TNF like a sponge.

And it gets more complex. Some studies show TNF inhibitors can actually cause a paradoxical effect. In rare cases, patients develop new inflammatory conditions-like psoriasis or even multiple sclerosis-like symptoms. Why? Because TNF isn’t just a villain. It helps keep rogue immune cells in check. When you remove it, some autoreactive T cells that were being held back start moving into places they shouldn’t, like the brain or spinal cord. That’s why neurologists watch patients closely for new neurological symptoms.

Another surprise: TNF inhibitors can make your body release more of a protein called sTNFR2, which should calm inflammation. But in some cases, that same protein triggers a feedback loop that actually makes more TNF. Science is still untangling this.

Who Gets These Drugs-and When?

TNF inhibitors aren’t the first line of defense. They’re the second. Or third. Doctors start with older drugs like methotrexate or sulfasalazine-called DMARDs. These are cheaper, taken as pills, and work slowly. If they don’t stop joint damage or control pain after 3-6 months, then TNF inhibitors enter the picture.

They’re used for:

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

- Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)

- Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (IBD)

- Plaque psoriasis

Studies show that 50-60% of RA patients on TNF inhibitors see a major improvement in symptoms and slowed joint damage. With DMARDs alone, that number drops to 20-30%. That’s not a small difference-it’s life-changing.

But not everyone responds. About 30-40% of patients eventually lose response over time. This is called secondary failure. Why? Often, the body starts making antibodies against the drug. It treats the biologic like an invader and knocks it out. When that happens, switching to a different TNF inhibitor might help-but sometimes, you need to move to a completely different class of biologic, like an IL-17 or IL-23 blocker.

The Risks: Infections, Cancer, and Paradoxes

Blocking TNF means weakening part of your immune system. That’s the trade-off.

You’re 2 to 5 times more likely to get serious infections. Tuberculosis is the biggest concern. That’s why everyone gets a TB skin test or blood test before starting. If you have latent TB, you’ll get antibiotics first. Fungal infections like histoplasmosis are also more common, especially in certain regions.

There’s also a small increased risk of certain cancers, particularly lymphoma. The absolute risk is low-less than 1 in 1,000 per year-but it’s real. That’s why doctors avoid TNF inhibitors in people with a history of certain cancers.

And then there’s the paradox. Some patients develop new autoimmune conditions while on TNF inhibitors. Skin rashes that look like psoriasis. Nerve inflammation. Even multiple sclerosis-like symptoms. It’s rare, but it happens. The reason? TNF inhibitors can’t cross the blood-brain barrier. So while they calm inflammation in your joints, they might leave inflammation in your nervous system unchecked-or even make it worse by disrupting immune balance.

Living With TNF Inhibitors: Real-Life Challenges

It’s not just about science. It’s about daily life.

Most TNF inhibitors are injected under the skin. That means learning how to give yourself shots. The first time is scary. The second time is awkward. By the third, it’s routine. But not everyone can do it. Some people have needle phobia. Others have arthritis in their hands. That’s why support programs from drug makers matter. AbbVie’s Humira Complete, for example, offers 24/7 nursing help, injection training, and even co-pay assistance.

Injection site reactions happen in 20-30% of users. Redness, itching, swelling. Usually mild, but annoying. Some people report fatigue, headaches, or nausea. And then there’s the mental load. Managing a chronic illness means constant monitoring. Blood tests. Doctor visits. Fear of infection. The emotional toll is real.

But the flip side? People talk about it in quiet tones. One woman on a patient forum said, “I went from needing a cane to hiking 5 miles. I didn’t think I’d ever feel my kids’ hugs without pain.” That’s the hidden win. It’s not just about being pain-free. It’s about being present.

The Future: What Comes After TNF?

TNF inhibitors changed everything. But they’re not the end.

Biosimilars-cheaper copies of brand-name drugs-are now widely available. Amjevita, a biosimilar to Humira, has taken about 25% of the market. That’s brought down prices and made treatment more accessible.

But newer drugs are coming. IL-17 inhibitors like secukinumab and IL-23 blockers like guselkumab are outperforming TNF inhibitors in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. They’re more targeted. Fewer side effects. Fewer infections.

Researchers are now designing next-gen TNF blockers that only block TNFR1-the bad actor-while leaving TNFR2 alone. TNFR2 helps regulate immune balance and even fights infection. If we can keep that part active, we might get the benefits without the risks.

For now, TNF inhibitors remain the backbone of biologic therapy. They’re not perfect. But for millions, they’re the reason they’re still here-still moving, still living, still hoping.

How long does it take for TNF inhibitors to work?

Most people start noticing improvement in 4 to 6 weeks, but full effects can take 3 to 6 months. Some feel better sooner, especially with infliximab infusions. Others need more time. If there’s no change after 12 weeks, your doctor may switch you to another drug.

Can I stop taking TNF inhibitors if I feel better?

Generally, no. Stopping the drug often leads to a flare-up of symptoms. In some cases, people who’ve been in remission for over a year may try to taper under close supervision, but most stay on therapy long-term. Autoimmune diseases don’t go away-they just go quiet. The drug keeps them that way.

Are TNF inhibitors safe during pregnancy?

Certolizumab pegol is the only TNF inhibitor proven to cross the placenta minimally and is considered safest during pregnancy. Others, like adalimumab and infliximab, can cross in the third trimester, so doctors often stop them around 20-24 weeks. Always talk to your rheumatologist and OB-GYN before planning a pregnancy.

Do TNF inhibitors cause weight gain?

Not directly. But some people gain weight because their inflammation drops and they start eating more or moving less. Others lose weight because their appetite returns after months of feeling sick. Weight changes are usually a side effect of improved health, not the drug itself.

What happens if a TNF inhibitor stops working?

Your doctor will check for anti-drug antibodies and assess your disease activity. If the drug has lost effectiveness, switching to another TNF inhibitor might help-but often, moving to a different class of biologic (like an IL-17 or JAK inhibitor) gives better results. Many patients respond well to a second-line biologic even after failing a TNF inhibitor.

Eddie Bennett

December 12, 2025 AT 04:54Man, I remember when my RA was so bad I could barely hold a coffee cup. Now I’m gardening on weekends and my grandkids climb all over me. TNF inhibitors didn’t fix me, but they gave me back the life I thought was gone.

Still takes a toll, though. Got a needle phobia and I still flinch every time I inject. But worth it.

Paul Dixon

December 12, 2025 AT 08:28Just had my 3rd Humira shot this week. Still weird seeing my own blood test results go from ‘inflamed mess’ to ‘meh, fine.’

Also, the nurse at the infusion center gave me a sticker that says ‘TNF Warrior.’ I frame it. It’s my new badge.

Vivian Amadi

December 13, 2025 AT 21:36Everyone acts like TNF inhibitors are magic but nobody talks about how many people get fungal infections or develop psoriasis from them. My cousin got MS-like symptoms after 18 months. They just say ‘rare side effect’ like that’s enough. It’s not. You’re playing Russian roulette with your nervous system.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 14, 2025 AT 06:29It’s wild how something so destructive-TNF alpha-was also essential for survival. Evolution didn’t design our immune system for modern autoimmune chaos. We’re patching a system that was never meant to be this broken.

Kinda makes you wonder if we’re treating the symptom or just fighting a ghost we created by living too clean, too long, too safe.

john damon

December 16, 2025 AT 03:22just got my cimzia injection today 🤞✨ no redness this time yayyyy

Monica Evan

December 17, 2025 AT 23:14My rheum doc said I’m a ‘high responder’-which is code for ‘your body didn’t hate the drug’

But here’s the thing nobody says: it’s not just the drug. It’s sleep. It’s stress. It’s cutting out sugar. I stopped drinking soda and my flares dropped 70%.

Biologics are a tool, not a cure. And yeah, I still cry sometimes when I see my swollen hands. But now I have the energy to cry in peace instead of in pain.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 19, 2025 AT 21:49There is a significant difference in pharmacokinetics between etanercept and monoclonal antibodies. Etanercept, as a soluble TNF receptor fusion protein, has a shorter half-life and does not induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). In contrast, adalimumab and infliximab bind to membrane-bound TNF and trigger immune cell lysis. This mechanistic distinction explains why some patients respond to one agent but not another, despite both being classified as TNF inhibitors. Additionally, the presence of anti-drug antibodies is more common with chimeric agents like infliximab, which may necessitate dose escalation or switching to a fully humanized alternative.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 19, 2025 AT 22:23So you’re telling me people are paying $20,000 a year to not feel pain? And you’re proud of it?

What about the real solution? Diet. Exercise. Sleep. But no, let’s just pump chemicals into people and call it progress.

And don’t even get me started on the pharmaceutical marketing. ‘Feel like yourself again!’ Like you were ever really yourself when you were in constant agony.

Kristi Pope

December 21, 2025 AT 08:03I’m 29 and on adalimumab. I used to think being ‘strong’ meant pushing through pain. Now I know being strong is asking for help, showing up even when you’re tired, and letting yourself heal.

My mom cried when I told her I could finally hug her without wincing. That’s the real win. Not the science. Not the stats. That moment.

You’re not broken. You’re just healing differently than everyone else. And that’s okay.

Aman deep

December 22, 2025 AT 03:18from india here and we dont have access to these drugs easily. my uncle had ra and they gave him methotrexate and he lost his job because he couldnt walk to work. now im studying biotech so one day maybe we can make these cheaper here. TNF inhibitors are life changing but they shouldnt be a luxury. i hope one day every patient gets a chance to walk again